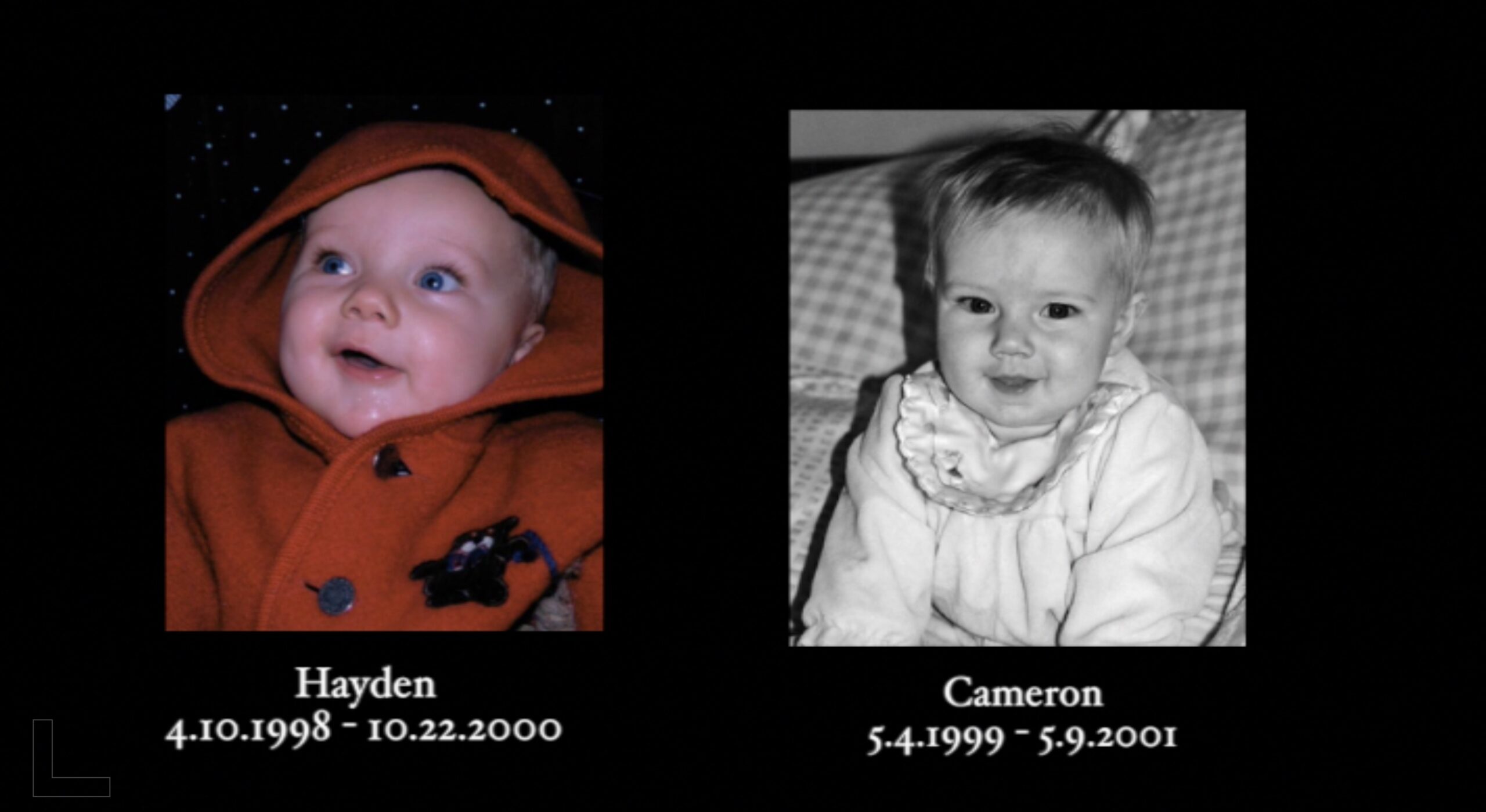

When my daughter Cameron and nephew Hayden were diagnosed with infantile Tay-Sachs in 1999, there were no treatment options that could help delay the progression of the disease; no promising therapies in the lab; no hope for help like that on the horizon. These two children were going to die in early childhood. Palliative care was the only option. (And I can attest that it made all the difference.)

Following Cameron and Hayden’s deaths, our family began fundraising and investing in research for treatments for lysosomal storage diseases, so that eventually it would be a different story for children and their families. We have been very involved with the National Tay-Sachs and Allied Disease Association (NTSAD), pooling our research grants with NTSAD Research Initiative’s Gene Therapy Consortium. (We also invest in palliative care. We believe they go hand-in-hand.) It is incredible to see how the landscape has changed since I was awakened to the world of rare disease, with the mapping of the human genome, the advancement in computing technologies, and new advancements in therapies, including gene therapy. For over 10 years now, NTSAD’s informal research mantra has been ‘Hope is on the horizon, Hope is on the horizon.’ And now, in 2020, the much-anticipated Hope has become the present moment: we expect the first-in-human gene therapy trial for a treatment for infantile Tay-Sachs this year.

This is incredible.

But ….

Now that we are here, I worry about what we are conveying with this word Hope. Unbracketed by caveats and a crash-course for families in what early-stage clinical trials really are – experiments – this word Hope in the context of a treatment feels somewhat treacherous.

I feel a kinship with every parent whose child is living with a rare and life-threatening disease. I feel a special, protective, aching love for every parent whose child is a pioneer in these early phases – they are courageous indeed. Considering the situation from my vantage point at Courageous Parents Network and at NTSAD, no longer needing something for my family, I feel protective worry for parents who hope the early-stage therapy will change the outcome for their child. In truth, for so many of these wretched, aggressive pediatric genetic diseases, the development of therapeutic treatments that will have significant impact on the child’s well-being and prognosis takes a very long time with many, many trials for multiple interventions. What we can hope for in the early days is something that will make the child’s quality of life a little bit better for a little bit longer. A little bit. And with the passage of time, the bits will hopefully get bigger and bigger until, as is the case with many childhood cancers, the prognosis is no longer a death sentence. But for now, the bits are likely very little.

This realization has taken several years and has been a hard pill for me to swallow. Ingesting it have has given me a stomachache. I’m quite serious. As I look at the families with young children recently diagnosed with Tay-Sachs, anxiously awaiting the opening of the first trial, I feel an unease born of understanding all too well what they hope for their child: being able to participate in the trial, having the therapy make a difference in ways that matter to them. I too hope for the best but I worry.

The rare disease world and the children who will be born affected years from now need these pioneering children and families who raise their hands to go first, and who must find a way to balance hope with realistic expectations. I think it must be very hard to be a pioneer when your heart is on the line. I never had to do that. The path for my daughter and family, for me and my husband, for my nephew and brother- and sister-in-law, was already charted and the outcome was known. Despite the deep sadness, there is a peace that can come with knowing what lies ahead and what one must do. We could plot our course.

Perhaps I needn’t worry about these parents. Perhaps they look at me and feel sorry that there was no such hope for my family. More likely, they intuit and appreciate the limitations, and will be happy enough to get that little bit better for a little bit longer. And hopefully that is enough. For now.