Things I wish providers had told me: 7 lessons learned raising my differently-abled son.

by Naomi D. Williams aka Noah’s mom

My son was born 14 weeks premature. The odds were not in his favor, yet he’s proven that he’s an underdog to bet on. During his five month stay between two neonatal intensive care units (NICU), I had many necessary yet hard and uncomfortable conversations with his care teams. I thought those would stop once we got home. I thought we were on our merry way to live our best life; but we were met with a barrage of soul-stealing and dream-crushing encounters. Each visit was an onslaught of apathetic and defeatist expectations. I understood the gravity of injuries sustained before, during and after his birth. I understood that I couldn’t change what had happened, but I could control how I interacted and loved him for however long he lived.

The purpose of this piece is two-fold. For providers, it is to offer context of the impact of your words and offer suggestions on how to maintain the integrity and severity of the present reality while using loving and compassionate language. For parents, it is to let those who find themselves in a similar situation know that you aren’t alone. Here are ways to embrace hard-to-process decisions, acknowledge your grief, and how to find joy through the journey.

Fair Warning: This piece will include terms that I heard during my journey as both a parent and a professional in the field. I have intentionally kept these words in this piece. I did this so we can: (1) get comfortable with the uncomfortable; (2) confront and begin to address personal biases; and (3) see or move beyond the negative and get to the business of making the most of the life and time that we have.

Love Unconditionally

I was a first-time mom, with a micro preemie who would have a long, challenging life ahead of him. Many follow-up appointments were met with “he’s so sick” or “he is failure to thrive” or “he’s neurologically devastated, he’ll never walk so we won’t fix his hips” or “he’s going to be mentally retarded and not able to do anything.”

While I appreciate candid conversations, a minor shift could have helped heal my hurts and lessen my grief just a little. A simple “he’s yours and you love him no matter what” would have gone a long way. Even more helpful would be to hear, “His life is valuable and has meaning. It doesn’t matter how long or short of a time he is on this earth. It doesn’t matter how neurologically typical or neurologically devastated he is, his life matters. Love him not because of what he can do or who he’ll become, yet love him because he is your child.” or simply “Disability isn’t the end of the world. Disability doesn’t mean less than.”

I wish his providers had said those things. It doesn’t negate the prognosis; it humanizes my experience as a mother.

Live Fiercely

Disability can help you learn how to live life to the fullest. My son and I have done more things with and because of his disabilities than those without a disability.

Once a friend wanted to do something BIG with Noah – a four-day, 158 mile self-supported bike ride in Colorado – and I agreed! We had no idea what we were doing or how we were going to get it done, but we were committed to figuring it out. We had to ensure we all hydrated sufficiently a week before traveling. We had to navigate the airports and planes with all of our stuff. We had to watch for altitude sickness (I got it the worst and had to be taken down a few thousand feet so I could breathe). This is just a snippet of logistics. What came from the trip was life altering. We all grew personally. We met and worked with people who had never been around a person with disabilities. Noah drove for the first time. His participation enabled the Colorado Track-Chair Program to receive a grant to help others with limited mobility access the park in a safe and comfortable manner. It was life-changing for all of us. You can read about it from our friend, Helen’s recap and watch the short video.

When we were sent home from the NICU and met with a barrage of specialists for lifelong appointments, I wish his providers would have said, “Create and live your (his) best life. Live to the best of your ability and don’t let disability be your limiting factor. Yes, there will be limitations, yet there are so many opportunities available if you learn how to adapt.” I also wish they would have encouraged me and shared the importance of making memories. I wish they had said, “Make memories. Every day you have breath is a gift and an opportunity to do, be, see, say more than the day before. Take advantage of the gift of time as you don’t know when it will run out.”

Noah and I have had many misadventures and we loved each one (not always in that moment). We learn and grow with every activity we attempt.

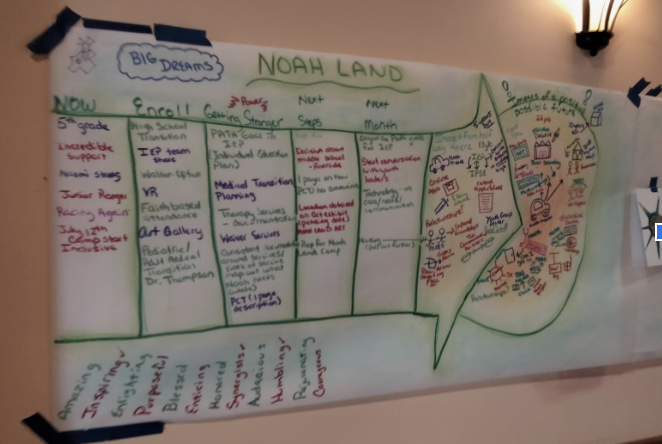

Dare to Dream

I had many dreams of what life would be like raising my child. I daydreamed what sports he would play and how I would teach him how to ride a bike. I planned out playdates with my friends and their children. I explored cloth diapers, making all his food, and even began looking into homeschooling curriculum. I was excited to take him on hikes and experience exploring nature together.

Many of those dreams were dashed when I was told he’ll never walk, talk, crawl or run. He’ll lose the ability to eat by mouth. That I could expect that he’ll be vegetative. As hard as that was to hear and more importantly to accept, I was committed to giving my son the best life and experiences that I could.

That meant we would try things and just see what happened.

Noah did crawl (not long or far, but he did it). He did walk (never unassisted but became skilled and confident as he walked the hall at therapy). He’s ridden a bike (he hasn’t had one of his own yet due to cost). He’s driven a power wheelchair and track chair (in the mountains of Colorado). He beats me in bowling and has completed more endurance races than I can remember (triathlons, half and full marathons with the assistance of friends lending their legs). Noah has gone rock climbing, kayaking, horseback riding, zip lining and many other fun yet unexpected adventures.

Is it perfect? Yes, perfectly imperfect! There is no such thing as perfect. Perfection is unattainable and pleasure-stealing for those that pursue it.

I wish his providers had said to me, “If you can dream or think it, dare to believe it, You can create it to happen. It may not look like everyone else and that’s okay.” Really, that’s the beauty of it because we’re all unique.

Remember, if your child never tries, you know what the outcome will be, so what’s the harm in trying?

Advocate Unapologetically

You know your child best. You know their likes and dislikes. You know when they are happy, sad, content, or mad. You know when they are sick, well, and pretending to be one or the other. You know their quirks, nuances, and idiosyncrasies. You know your child, and what makes them unique. By knowing your child, you are their voice, until they can use their own. If you don’t speak up, who will? Providers do their best with the information that is presented, combined with their education and experiences. They are an expert in their field, and you are an expert of your child and family unit. Speak up so (and until) you and your child’s voice is heard.

Once it had been nearly 20 hours since Noah had been awake, alert, and active. This was not his norm. I took him to the emergency department, and he was admitted to the hospital. His health and demeanor continued to decline, yet it was overlooked because providers assumed this behavior was his baseline (due to his chart, diagnoses, and severity of medical complexity). I tried very hard to share and explain what baseline looked like for Noah and that there was something very wrong with him, despite me not knowing what was wrong. Thankfully a physician who was an active member of his specialist team, had cared for Noah for several years and knew what his baseline looked like, was assigned the case. With his help, we were able to identify one of the problems and begin to address it. What began as c.Diff morphed into toxic megacolon and septic shock in a span of 48 hours. It was a tumultuous hospitalization and experience. It was slow, yet Noah began to recover. His baseline attitude, demeanor, and infectious smile began to show up again. I captured him on video and began to show the team that initially cared for him at the beginning of this hospitalization. They were in total awe and disbelief that they were looking at the same kid.

I wish his providers had said to me, “Be assertive while remaining respectful. You are a vital member of the care team. You bring the story together and bring the whole picture into focus.”

Hope for the best yet prepare for the worst

As your child gets older, things may get harder if their condition doesn’t get better. Fortunately, or unfortunately, medical equipment has slowly been making its way back into our home. I’m thankful to have it and saddened that my son needs it. It’s a constant reminder to live a good life so we can have a good death. Remember to acknowledge and celebrate the inchstones that make up the milestones even if unrelated to a diagnosis.

As he was born 14 weeks early, I knew the odds of survival were not in my son’s favor. There were conversations and a little bit of (death) preparation during his first month of life. For kids born prematurely, you might be having these generic conversations regarding risk and outcomes when various surgeries are scheduled. I wish my care team and I would have had the hard conversations about what a good death means to us and what that looks like. I wish his providers would have said, “Let’s talk about allowing natural death (AND) instead of only a do not resuscitate order (DNR).”

This type of conversation allows for parents to make hard, yet loving decisions.

Be prepared for the normal even when everything is so different

Doctors repeatedly told me what my son wouldn’t do. He won’t crawl, walk, or talk. He’ll lose the ability to eat and swallow safely. He will be mentally retarded and be unable to learn. With this type of message reiterated for years, why on earth would I believe that we’d ever reach puberty, let alone transition through it? Specialists who cared for my son ask, “How is Noah?” and we have general conversation. I give brief updates on his most recent or upcoming adventure. But before letting them go I’ll say “You told me everything not to expect, you didn’t tell me about tents in pants. I’m having a hard time with this.” I usually get a blank stare and then the light bulb goes off, releasing a grin or a burst of laughter. I wish his providers would have said, “Even as so much of Noah’s life is different, he is still a boy, and he might experience some of the things other boys do.” I wish that when I brought up these typical things, the clinicians were courageous enough to provide guidance.

This would have prepared me for some typical experiences any other parent faces.

Listen carefully because sometimes the advice is there

I received two pieces of advice that have been my lifeline. Early on in our NICU journey, a nurse said, “Grieve your expectations. Grieve what you thought would be so you can enjoy what you have.” Although I didn’t fully grasp what she meant at the time, life events have described and defined the meaning. Those words have served me well over the years. I’ve learned how to acknowledge the feelings that come with the losses, while giving gratitude for the inchstones that make up the milestones.

“Find joy through the journey” was the other piece of advice given to me by the neonatologist that delivered my son. The first few months of my son’s life were riddled with life-altering events and conversations. Knowing the road would be a long, arduous, and emotionally charged one, this doctor gave me a gift. He planted the seed that happiness is a choice and something that I had control over. The trajectory of my son’s life was likely to be hard, frustrating, and sad, but I had the opportunity and choice to decide what I focused on. I opted to look at our time together as taking the scenic route to our destination. We would and continue to embrace the bends in the road (setbacks) and we wait with anticipation and expectation for the things that we’ll see and experience that wouldn’t be found had the direct route been taken.

Please hear me when I say disability isn’t the end of the world. Yes, it’s different. Yes, it can be lonely. Yes, it’s challenging, but so is life. The attitude and outlook you have greatly influences the journey and outcome. Prognosis isn’t synonymous with quality of life.

I wish providers would have told me that.

Hear more from Naomi by viewing her video interview.