2/28/2021

·Enable high contrast reading

The Trials of Clinical Trials

CPN is honored that the Byers family has agreed to share and reflect on their experience of having their son Will participate in two very different clinical trials. In Part One of this narrative, Will’s mother, Valerie sets the stage for Will’s participation in the first trial and discusses the clinical trial process, in particular the complex decisions they faced and the myriad of emotions that accompanied them.

Part One of the Trials of Clinical Trials

The Call

The vibration in my pocket started while I was lying on my back, the dentist massaging my gums as he inserted multiple shots of Novocaine into the back of my mouth. My phone made the familiar buzzes of an incoming call and then a short buzz to let me know I’d missed the call. Another single buzz followed, letting me know there was a voicemail.

“Can you feel this? Does this hurt?”

Oddly enough, the root canal, the repercussion of an old filling that had cracked, was the least of my worries. The truth was that, while I couldn’t feel anything in my mouth, everything about me was hurting. It was the worst week of my life. My chatty, loving, creative, and joy-filled 4-year old son, Will, had been given a death sentence when geneticists confirmed that he had Sanfilippo Syndrome. Sanfilippo Syndrome is a rare genetic condition in which a person is missing a critical enzyme used in ridding the body of cell waste. This waste then builds up in every system of the body and causes cell damage and death. It would eventually rob my son of his ability to talk, eat, and walk and then take his life. To look at him running around outside in the warmth of our Texas spring singing songs from his favorite cartoons inspired both disbelief – how is this even possible?…… and heartbreak – he will lose his ability to do this and I will lose him.

There is no cure or treatment for Sanfilippo Syndrome. It’s not for want of trying. Since the discovery of the condition in 1963, parents and scientists have been working against time to try to find a mechanism to slow, stop, and/or reverse the disease’s effects. However, as with many rare diseases, the money and interest in combatting the condition is limited. Work comes from the grassroots efforts of affected families and dedicated researchers. While the effort and commitment level in these parties is high, the reality is that without large-scale public funding and momentum, many children live and die with no hope of anything other than the standard progression of the disease.

There is no cure or treatment for Sanfilippo Syndrome. It’s not for want of trying. Since the discovery of the condition in 1963, parents and scientists have been working against time to try to find a mechanism to slow, stop, and/or reverse the disease’s effects. However, as with many rare diseases, the money and interest in combatting the condition is limited. Work comes from the grassroots efforts of affected families and dedicated researchers. While the effort and commitment level in these parties is high, the reality is that without large-scale public funding and momentum, many children live and die with no hope of anything other than the standard progression of the disease.

With so many rare diseases lacking official treatments, the hope of many rare disease families comes in the form of clinical trials. They seek out the researchers specializing in the rare condition, talk to them, see if there is any option for clinical trial enrollment. If there is no clinical trial, then the families look to see where the research is at and begin fundraising to help support the current work with the goal of getting the research to a clinical trial point. Largely, they do this work with the hope that their child or family member may be able to participate should a trial come to fruition.

We were no different. Although newly diagnosed and grieving the dreams that we had for our son’s life, we jumped in to trying to wrap ahead around this disease and look for something, anything, we could do to help Will. One of the first things we did was begin to connect with other families. We wanted to know what they knew, to understand the journey they had been taking and that we were just starting. These families quickly became our lifeline. They understood exactly where we were and what we were feeling in a way no one else in our lives could. One family even ended up giving us a chance at life for Will.

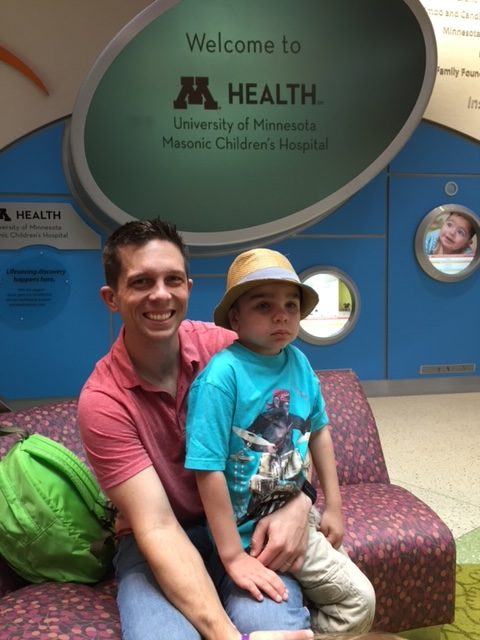

Leaving the dentist, root canal over and my mouth as numb as my soul had been for a week, I took out my phone to listen to my voicemail. “Mrs. Byers, this is Dr. – with the University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital. I’ve heard from another family that your son, Will, is 4-years old and was recently diagnosed with Sanfilippo Syndrome, Type B. I just wanted to let you know that we are currently recruiting for a clinical trial for his condition and have limited spots remaining. Please call me back and let me know if you’d be interested in having your son screened for the trial. Thank you.”

My heart stopped and a small seed took root in that stillness and began to grow a feeling I hadn’t felt that week: hope.

The Chance

Our phone call was an oddity – you just don’t get diagnosed with Sanfilippo Syndrome and then get a phone call that same week asking you to come screen for a clinical trial. It was simply the luck of having connected to the right people at the right time. In this case, we had connected with another family screening for a different clinical trial at the same location just as a clinical trial for our son’s subtype of Sanfilippo was actually recruiting for participants. Sanfilippo Syndrome, especially in 2015, had an extremely low number of clinical trials recruiting. And by small, I mean two – 0ne for the more common subtype,Type A and one for the more rare Type B, which is the subtype Will has.

The more likely process for rare disease families is to stalk the clinical trial website daily investigating the listed trials, trying desperately to understand unfamiliar research terminology and gain an unofficial medical degree overnight. You watch for “Active, not recruiting” to change to “Recruiting.” You call and email the clinical trial coordinators and then call and email again when they don’t respond back to you soon enough. Then you have your local doctors call and email on your behalf, hoping they will get a response. You struggle to understand, when your loved one is literally dying a little more every second of every day, how clinical trial administrators can just react without your sense of life-or-death urgency. You curse the very guidelines and bureaucracy that you know are designed to keep participants safe for delaying the one thing that could actually make a difference in your loved one’s prognosis. You see the limited number of spots available and feel guilty about competing with other families facing the same journey you are on while also doing everything in your power to give your loved one a chance. Even here, right at the beginning, you feel the stress of this process. But you also feel invigorated because, in a situation where it seems like you can do nothing to make it better, you are able to do SOMETHING. You made a promise to provide the best care possible and this is how you are going to do it. You double down on your resolve and keep emailing.

The more likely process for rare disease families is to stalk the clinical trial website daily investigating the listed trials, trying desperately to understand unfamiliar research terminology and gain an unofficial medical degree overnight. You watch for “Active, not recruiting” to change to “Recruiting.” You call and email the clinical trial coordinators and then call and email again when they don’t respond back to you soon enough. Then you have your local doctors call and email on your behalf, hoping they will get a response. You struggle to understand, when your loved one is literally dying a little more every second of every day, how clinical trial administrators can just react without your sense of life-or-death urgency. You curse the very guidelines and bureaucracy that you know are designed to keep participants safe for delaying the one thing that could actually make a difference in your loved one’s prognosis. You see the limited number of spots available and feel guilty about competing with other families facing the same journey you are on while also doing everything in your power to give your loved one a chance. Even here, right at the beginning, you feel the stress of this process. But you also feel invigorated because, in a situation where it seems like you can do nothing to make it better, you are able to do SOMETHING. You made a promise to provide the best care possible and this is how you are going to do it. You double down on your resolve and keep emailing.

And let’s say you make it—you get the call or the email telling you that your loved one is eligible for pre-screening as we did. You are excited but what comes next isn’t easy either. It means putting your child through more bloodwork and having doctors do and send more paperwork until finally you get the go ahead to travel to the trial site for the official screening process. When we were invited to screen, we needed to find childcare for our daughter, take time off of work, and travel across country with a child with special needs. We then had to put our son through more medical procedures along with day-long cognitive and developmental testing. We did this all with the constant reminder that only 11 participants were being admitted into this trial. Would our son be one of them?

The Choice

When going to screen for a clinical trial, there are actually two evaluations happening simultaneously. The first and obvious evaluation is that the clinical trial team is assessing the potential participant to see if the individual meets the criteria to be included in the trial. Second, the participants (and their family) are evaluating the trial to see if it meets their expectations. Or at least they should be.

The power differential is very obvious in rare disease clinical trial evaluation. Because the disease is rare, families don’t have multiple options from which to choose. And because these rare diseases can often be fatal or life-limiting, families don’t have the time to wait for more options to become available. Often, due to the cost of experimental treatments for rare disease, participation slots in the trial are limited. This raises the urgency rare disease families feel when being offered a chance for a clinical trial and puts the majority of the power in the hands of the clinical trial provider. When families feel this heightened urgency and sense of competition for inclusion in the trial, it is difficult for them to have the necessary space and resources available to assess their risk tolerances. To families, the trial treatment could very well be the difference between life and death for their loved one. It’s a great deal of pressure to put on a family already living the nightmare of a difficult diagnosis.

Receiving an offer of a clinical trial screening opened up a door to a level of hope that we hadn’t even allowed ourselves to contemplate. Upon arriving in Minnesota from Texas, we were overwhelmed by the situation. We were still freshly diagnosed and reeling from the thought that our active 4-year old was actually slowing dying from a terminal genetic disease that we had unwittingly passed on to him. Will had always been a healthy kid overall, so we were unprepared for the toll the multiple medical tests, developmental tests, and hours in hospital rooms would take on us during the evaluation. There were so many questions to consider, so many terms to understand. However, even as we faced these emotional challenges, we would also feel remorse about feeling overwhelmed. It was hard to navigate our feelings regarding the clinical trial evaluation because it felt like questioning a huge gift. We were being SCREENED FOR A CLINICAL TRIAL barely 2 months after diagnosis. We felt the full weight of that privilege. We knew how many other families would give anything to be where we were right then, being evaluated for a CHANCE at a potentially different outcome for our child. How could we turn down such an opportunity?

There are assumptions about rare disease families within the clinical trial space. It is presumed we will jump at the chance of participating in a clinic trial and immediately embrace being participants if offered the opportunity. Many of these assumptions come from a well-meaning belief that these families will participate in clinical trials because it is the only hope their loved ones have of an improved quality of life. However, what that improved quality of life looks like is up to the families, not to the researchers. There are so many things to consider, not the least of which is that a clinical trial is just that: a trial, and one that fulfills multiple definitions of that word. First, it is a trial in that it is an experiment. Neither the participants nor the researchers can say for certainty that the trial will help; no one knows the outcome. No one knows if it will help, or if it will do nothing, or if it will hurt, or if it will cause issues that might be worse than the issues already expected with the course of the disease. Secondly, it is a trial because it is a test of faith and endurance through subjecting oneself through hardship. This includes the participant and the support network of the participant. Trials require medical care and testing, potential side effects, travel, expense, personal documentation…the list goes on. Participating in a trial is a job within itself; it is an endeavor and one that can burn people out quickly if their expectations from the trial are not met.

There are assumptions about rare disease families within the clinical trial space. It is presumed we will jump at the chance of participating in a clinic trial and immediately embrace being participants if offered the opportunity. Many of these assumptions come from a well-meaning belief that these families will participate in clinical trials because it is the only hope their loved ones have of an improved quality of life. However, what that improved quality of life looks like is up to the families, not to the researchers. There are so many things to consider, not the least of which is that a clinical trial is just that: a trial, and one that fulfills multiple definitions of that word. First, it is a trial in that it is an experiment. Neither the participants nor the researchers can say for certainty that the trial will help; no one knows the outcome. No one knows if it will help, or if it will do nothing, or if it will hurt, or if it will cause issues that might be worse than the issues already expected with the course of the disease. Secondly, it is a trial because it is a test of faith and endurance through subjecting oneself through hardship. This includes the participant and the support network of the participant. Trials require medical care and testing, potential side effects, travel, expense, personal documentation…the list goes on. Participating in a trial is a job within itself; it is an endeavor and one that can burn people out quickly if their expectations from the trial are not met.

When assumptions and expectations do not align, it can lead to a discord between the family and the clinical trial providers, especially if a family initially chooses to be part of a clinical trial without having the time, space, and guidance to fully evaluate their decision. Rare disease families can become disillusioned and decide the burden of the trial is too much to bear. They may experience regret and ultimately decide to leave the trial, which then puts the study itself in jeopardy. It is a delicate balance. It is important we afford rare disease families the space to assess their dignity of risk; that is, allowing them their right to determine what level of risk they are willing to take on that fulfills their definition of quality of life. This could be that they decide to live with the risk of a clinical trial or that they decide to live with the risk of their condition, untreated. Whatever decision a family makes, it must be met with support.

In our case, we sat with our options upon returning home to Texas from Minnesota as we waited to hear if Will would be officially invited to participate in his trial. We reviewed literature, talked with experts, and just held our son, the happy little boy who was completely oblivious that there was anything different about him. When the call came, telling us that Will was a fit for the trial and asking us if we would like to go forward, we said yes.

Coming Soon: Part Two: Valerie shares Will’s participation in the clinical trial, which ultimately was halted by the trial sponsor.

Valerie Tharp Byers, EdD is a psychology and education researcher who lives in Spring, Texas with her husband, Tim, and children, Will and Samantha. Valerie became a rare disease advocate in 2015 following the diagnosis of Will with Sanfilippo Syndrome, a degenerative and fatal genetic disorder. Valerie is a Board Member of the Cure Sanfilippo Foundation, where she works to raise both the public profile of Sanfilippo Syndrome and the funds necessary to support research and clinical trials. Valerie and Tim also co-founded and operate WILLPower, an organization in their local area dedicated to raising Sanfilippo Syndrome awareness.

Valerie Tharp Byers, EdD is a psychology and education researcher who lives in Spring, Texas with her husband, Tim, and children, Will and Samantha. Valerie became a rare disease advocate in 2015 following the diagnosis of Will with Sanfilippo Syndrome, a degenerative and fatal genetic disorder. Valerie is a Board Member of the Cure Sanfilippo Foundation, where she works to raise both the public profile of Sanfilippo Syndrome and the funds necessary to support research and clinical trials. Valerie and Tim also co-founded and operate WILLPower, an organization in their local area dedicated to raising Sanfilippo Syndrome awareness.