9/7/2021

·Enable high contrast reading

The Ache of Bigger But Not Better

Colson’s first birthday arrived like a miracle. The rapid progression of his mitochondrial disease during his first year was stifling. For him, me, and his daddy to reach the big ONE was a much-needed boost to our frayed psyches. Colson turning two, then three, were similarly momentous occasions. They were simply birthdays we didn’t think we’d get. By the time he turned four last October, I had made the fatal mistake of accepting his birthdays as a matter of fact rather than a miracle of medicine. As his fourth birthday approached, I struggled with the knowledge that Colson was no longer a baby, nor was he even a toddler. At four, Colson became a big boy in my eyes, and that shift ached.

Colson’s first birthday arrived like a miracle. The rapid progression of his mitochondrial disease during his first year was stifling. For him, me, and his daddy to reach the big ONE was a much-needed boost to our frayed psyches. Colson turning two, then three, were similarly momentous occasions. They were simply birthdays we didn’t think we’d get. By the time he turned four last October, I had made the fatal mistake of accepting his birthdays as a matter of fact rather than a miracle of medicine. As his fourth birthday approached, I struggled with the knowledge that Colson was no longer a baby, nor was he even a toddler. At four, Colson became a big boy in my eyes, and that shift ached.

My growing pains when Colson turned four are likely familiar to many parents here. His peers, beloved children of my closest friends, were entering pre-K, fully potty trained, speaking in full sentences, and developing unique interests like Legos and Paw Patrol and make-believe food service stands. Developmentally, Colson remained an infant. Approaching four, the gap which had always existed between Colson and his peers became a black hole. I struggled tremendously to engage him in a way that promoted his dignity and was appropriate for his chronological age. He had always been my baby. I spoke to him, held him, protected him, and moved him through the world like my baby. But I did not want to infantilize him, so I made changes where I could.

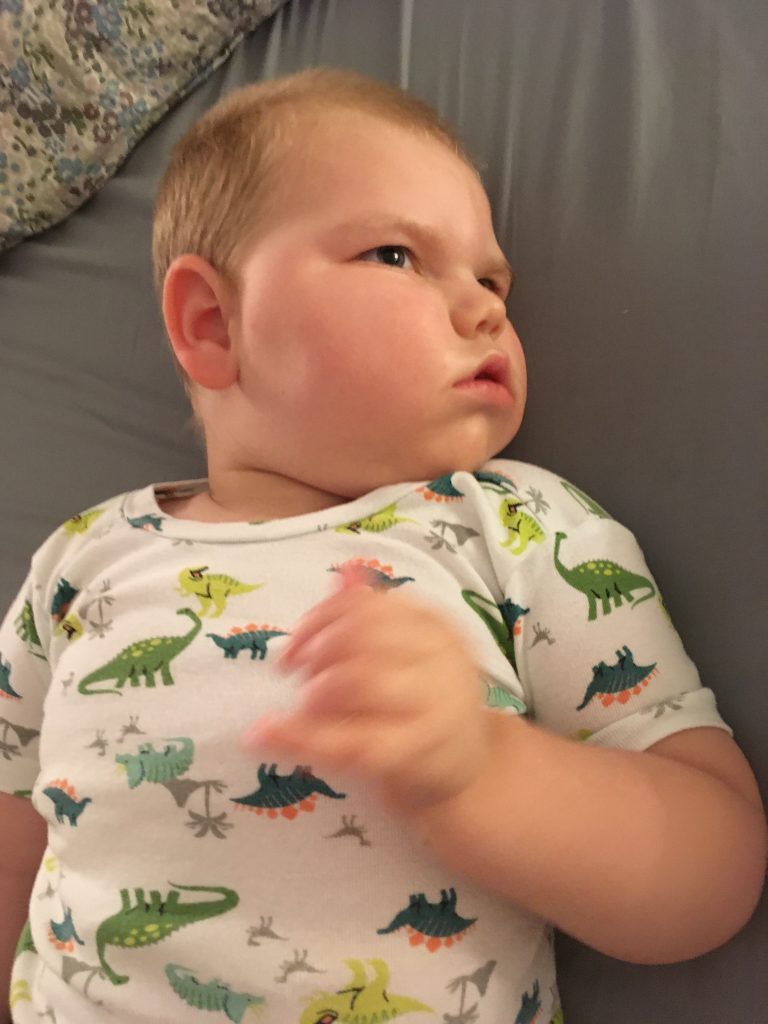

I swapped his washcloths decorated with baby ducks and little foxes for a new set with dinosaurs and whales. I upgraded his small gray diaper bag to a bigger, sleeker, navy blue backpack. I ordered booties to cover his orthotics and complete his outfits, after shunning shoes his entire life. I tried (though frequently failed) to stop talking to him in baby talk and speak to him in direct sentences with age-appropriate language. You know, big boy stuff.

But just because we could change the accoutrements didn’t mean we could change the complexity of his care. In fact, as he grew, his symptoms became worse. Where the differences between him and his peers had once split like tributaries on a stream, they began flowing like completely different rivers. At almost four, Colson was diagnosed with hip dysplasia due to his immobility. He developed curvature in his spine, which would inevitably turn into scoliosis. He become obese, despite only being able to tolerate 15 ounces of formula a day. (For reference, a two month old can tolerate 24 – 40 ounces in the same period).

The biggest moment of awareness about what our future with a medically complex big boy would look like came just a few weeks before his fourth birthday, when he was hospitalized for abnormal seizure activity. A nurse asked me if he was on a turning schedule, and I looked at her with total incomprehension on my face. She explained that many children with immobility get put on turning schedules as they grow in order to avoid bedsores. The thought of bedsores on my boy’s perfect, soft, unblemished skin made me weep. Made me afraid for his future. But we had lived through tearful transitions before, and we would do it again.

The biggest moment of awareness about what our future with a medically complex big boy would look like came just a few weeks before his fourth birthday, when he was hospitalized for abnormal seizure activity. A nurse asked me if he was on a turning schedule, and I looked at her with total incomprehension on my face. She explained that many children with immobility get put on turning schedules as they grow in order to avoid bedsores. The thought of bedsores on my boy’s perfect, soft, unblemished skin made me weep. Made me afraid for his future. But we had lived through tearful transitions before, and we would do it again.

Shortly after that hospitalization, I spent ninety minutes on the phone with his various speciality clinics, getting appointments lined up for the next six months. We were going to hit four head-on. And then, in a matter of hours last December, less than two months after that fourth birthday, Colson succumbed to Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. His respiratory system had always been compromised, and it finally had enough. As what would be his fifth birthday approaches this October, I find myself in the excruciatingly tight corner of perverse relief and profound grief.

Parents of complex kids must grow around our sorrow and uncertainty as our kids grow in their bodies. If we are lucky, they also grow in their development. But for too many of us, regression lurks like a menace. Watching Colson slowly lose his smile and laugh was agonizing. I lived in constant dread that he would lose his sing-song voice. I was wrecked by the idea of him getting too big for me to hold on the couch or snuggle in bed. I miss that voice, and I miss that body. But I don’t miss watching him fade, nor do I miss watching his symptoms get worse. I am so relieved that I was able to take steps towards Colson’s future, despite my trepidation of his emerging big boy status. Knowing we had both hospital-based and community-based palliative care in place gave me confidence that that transition would be possible. When palliative care providers help families explore these points of transition and name the growing pains, they make these otherwise painful pivots meaningful and, perhaps, even hopeful.

Liz Morris loves exploring complex questions. Her professional experiences in project management, librarianship, and community development prepared her well for her favorite role as mom to Colson. Colson, impacted by mitochondrial disease since birth, inspired Liz to face the complicated aspects of his life through writing and advocacy. Liz serves as a family advisor at Seattle Children’s Hospital, and is a volunteer ambassador for the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation. She is committed to helping families find the information they need to help them live well in the face of life-limiting illness. You can find Liz on Instagram @mrsliz.morris

Liz Morris loves exploring complex questions. Her professional experiences in project management, librarianship, and community development prepared her well for her favorite role as mom to Colson. Colson, impacted by mitochondrial disease since birth, inspired Liz to face the complicated aspects of his life through writing and advocacy. Liz serves as a family advisor at Seattle Children’s Hospital, and is a volunteer ambassador for the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation. She is committed to helping families find the information they need to help them live well in the face of life-limiting illness. You can find Liz on Instagram @mrsliz.morris