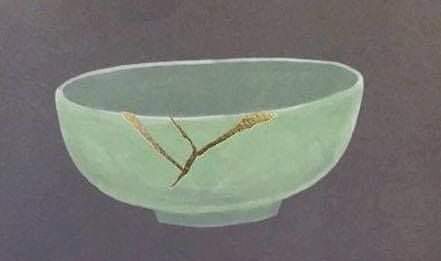

There is a tradition in Japanese pottery known as kintsugi (disclaimer: I am not of Japanese heritage nor will I pretend to understand or explain the breadth of this process; please see the Internet for an exhaustive history & description).

There is a tradition in Japanese pottery known as kintsugi (disclaimer: I am not of Japanese heritage nor will I pretend to understand or explain the breadth of this process; please see the Internet for an exhaustive history & description).

I have never encountered a bowl or cup created in this style but the process is deeply ingrained in my mind. It exists inside me as a folktale, a story that strikes you as charming as it is read before bed, but has the power of provocation, to wake you in the middle of the night with thoughts deeper than the surrounding darkness.

If I were to craft kintsugi into a folktale, the story would be broken into three movements and it would go something like this:

- A large bowl is hand-crafted, hand-painted, lacquered. It is treasured.

- The bowl shatters at the hands of the great-grandchild who inherited this heirloom. Its pieces are cast into a box, placed in a dark corner of the basement, and even one glimpse of the box brings sadness, shame, regret at having broken such a treasure.

- The bowl’s great-great-great-granchild discovers the box, ushers the pieces back into the light, and joins the shards together once again. The cracks are filled with a mixture containing gold, which makes the bowl stronger, more beautiful, more resilient than before.

That is the cycle of kintsugi: created, broken, repaired and restored and redeemed. The culture that birthed this technique does not disguise brokenness; rather, it displays it; the story and history of the object is not hidden or covered up; rather, it is honored. I have to let this sink in each time I reflect upon this artform; the repaired cracks are on full display and they are what makes the piece more beautiful.

I am not sure that the Japanese craftsmen intended kintsugi to be a metaphor for humankind, but I frequently find myself imagining that I am the bowl. My child, my son, is currently the largest piece of me; his body was created broken when one piece of his DNA was swapped for another.

The medical community calls him complex, and he certainly is, but his palliative care provider calls him fragile. Camden’s body and life, they are fragile. As his mama, full-time caregiver, and home health nurse, I have become fragile. I exist in the fragile space between life and death as I live with my son and know death will come far too soon. I am the bowl and I am constantly faced with my shattered self.

What would happen if, instead of denying my reality, I gathered each one of the broken pieces of my heart, mind, and body, and set my eyes on the road ahead? What if I released the ideas of what could have been and sought out gold to craft a new, more beautiful, increasingly resilient shape? What if I could accept that being fragile was what I was always meant to be, and wearing my scars on my sleeve was what set others free?

Megan Devine, author of It’s Okay to Not Be Okay, writes about grief as something not to be fixed or removed or left behind, but as something that requires tending. I must learn to carry this, my grief, along with me.. This shall be my lifelong pursuit.

Each day that I am gifted with Camden’s presence in this world, I am offered a choice. I can choose to allow my grief to keep me in chains and weigh me down. Or, I can tenderly gather the pieces of myself, acknowledge my grief and invite it along, embrace my fragile boy, and celebrate each moment we spend side-by-side.

Each day that I am gifted with Camden’s presence in this world, I am offered a choice. I can choose to allow my grief to keep me in chains and weigh me down. Or, I can tenderly gather the pieces of myself, acknowledge my grief and invite it along, embrace my fragile boy, and celebrate each moment we spend side-by-side.

And I have come to believe that it is the celebration and the gratitude for each moment together that creates the gold, and each nugget of gold shines a bit more light into my darkness. I cannot repair Camden’s broken DNA, or all of the organ systems that were subsequently impacted, but I can be the gold and the light that carries him through his time in the world.