Theme: Pediatric palliative care benefits

With over 8.2 billion people across 195 countries, humanity is shaped by diverse societal norms, cultural differences, physical appearances, languages, religions, community structures, and traditions. However, two universal experiences connect us all: life and death.

The UN estimates that approximately 385,000 babies are born each day—around 140 million each year. The impending arrival of a child brings immense tradition, cultural norms, and hope. Celebrations, anticipation, and excitement surround each birth, whether it occurs in a hospital or a tribal community. New parents often receive books and advice on child-rearing, and a network of support from doulas, midwives, and medical professionals helps welcome each child into the world. Society generally expects us to watch our children grow into responsible adults who contribute to the greater good.

Birth has a clear timeline; a gestational period of 40 weeks is universally accepted as full term. In stark contrast, there is no roadmap for anticipating the imminent death of a child. If one is fortunate, they may be given time to make the most of their moments together. This time is often marked by a dichotomy of gratitude for each day of life, alongside fear and anxiety about what the next day may bring.

When we signed our last discharge forms for our daughter after deciding to pursue palliative care, I felt two powerful emotions: a sense of failure for not being able to do more and relief that she might finally be pain-free. Unlike the countdown to birth, we had no timeline for her remaining days. Our daughter had never celebrated a birthday at home; including the day she was born, she spent three of her birthdays in the hospital. As her mother, my only wish was for her to celebrate her fourth birthday at home, surrounded by love and joy, because she was our light. As a medical parent, I faced the harsh reality that the next birthday might not happen.

With two medically complex children receiving concurrent treatments for rare diseases, we had never spent time together simply enjoying our family of four. Thanks to a compassionate palliative care team and Make-A-Wish, we were able to take our daughter to the seaside cliffs and misty coastline of Big Sur. While the trip was filled with smiles and love, there were also moments of fear when her vitals approached a point that could lead to hospitalization in an unfamiliar place. Looking back, the overwhelming emotion we felt upon returning home was relief that our daughter did not pass away in a new hospital surrounded by strangers. I also felt a sense of guilt, knowing we were one of the lucky few families to experience such a trip.

Not long after, we celebrated our daughter’s birthday at home, inviting our closest friends, aware that we might need to cancel at any moment. As parents, we are seldom prepared for such unknowns. Today, we cherish those party pictures more than anything, as they remind us of something we never anticipated would happen.

Shortly after her birthday, I asked our palliative care team for a meeting, overwhelmed by a sense of panic. I expressed how unprepared I felt for the possibility of losing her. Fear of the unknown consumed me—where would it happen, how, and who would we call? We were unfamiliar with cultural practices surrounding death and did not know what to do afterward. At that time, our then 4-year-old daughter was surprisingly active, crawling and pulling up to stand, seemingly unconcerned by our discussions. The medical team was surprised by her progress, and we laughed about how I was overthinking everything as a typical medical mom. My husband and I had envisioned a plan for that day, involving our almost 10-year-old son as a vocal advocate and caring big brother.Our son had been an integral part of the medical care we had provided for our daughter and wanted to be involved in her end of life planning as well.

Then, the day we dreaded arrived, and everything unfolded differently than we had imagined. We experienced a pain unlike any we had known before. Our daughter brought us light, purpose, love, and joy. The one thing we could give her that day was the freedom to finally be pain-free and at peace. This realization helped us navigate that day and the days that followed, thanks to our palliative care team, who understood we were venturing into uncharted territory.

We expect our children to outlive us and care for us as we grow older. We envision our children living long, healthy lives, and the idea of a parent burying or cremating a child feels unfathomable. Society is not structured to support parents facing such loss, and when it occurs, the experience can be isolating and filled with sadness. While some child deaths can be sudden, others follow a long, painful journey where all options have been exhausted.

If our children cannot outlive us, we must create pathways to help families process this overwhelming life event differently—with knowledge and acceptance that this is part of the circle of life.

Parvathy was a member of our first class of Parent Champions. Learn more about her here.

Theme: Pediatric palliative care benefits

Theme: Pediatric palliative care benefits

When I think about my path to becoming the pediatrician I am today, I think about my mother. My mother, who loved so deeply, especially her children. She would look at my sister and I each day, her eyes seemingly as large as the world itself, filled with hope and conviction to see us live out every great possibility for our lives beyond what she could ever imagine for herself. She was tiny, standing 5’1” tall (and always wanted to be 5’10”, which I grew to be). But oh, was she mighty. My mother, who grew up in abject poverty in the New York City housing projects, earned her GED as a teenage mother, and ultimately climbed the corporate ladder of the New York City real estate banking industry during Wall Street’s hay day. My mother, who survived childhood trauma that was unimaginable and went on to parent with the kind of love that was wide and vast and could seemingly heal any skinned knee or heartbreak. My mother…who always advocated for us, never gave up on us, and desired nothing more than to see us live our best lives.

When I think about my path to becoming the pediatrician I am today, I think about my mother. My mother, who loved so deeply, especially her children. She would look at my sister and I each day, her eyes seemingly as large as the world itself, filled with hope and conviction to see us live out every great possibility for our lives beyond what she could ever imagine for herself. She was tiny, standing 5’1” tall (and always wanted to be 5’10”, which I grew to be). But oh, was she mighty. My mother, who grew up in abject poverty in the New York City housing projects, earned her GED as a teenage mother, and ultimately climbed the corporate ladder of the New York City real estate banking industry during Wall Street’s hay day. My mother, who survived childhood trauma that was unimaginable and went on to parent with the kind of love that was wide and vast and could seemingly heal any skinned knee or heartbreak. My mother…who always advocated for us, never gave up on us, and desired nothing more than to see us live our best lives.

My nickname growing up, which she and my father gifted to me, was “the first to come and stay.” She lost two children prior to my birth, one as a toddler to a catastrophic head injury and the other shortly after birth to congenital heart disease. I will never fully understand the complexity of her losses and the void they created. But the tentacles of grief from their deaths extended into our lives and were ever present, touching us and twisting about our family dynamics. Despite this, there was so much that my mother protected me from. I do not know everything about the pain she endured in losing my brothers. But I did come to know that there was care she didn’t have access to as my eldest brother was brought to the hospital that might have saved his life. And there was care she didn’t have access to when she was pregnant with my second brother that might have saved his life. She didn’t have access to this care because of where she lived, what she wasn’t taught, who wasn’t there to advocate for her, and what value wasn’t placed on her life and that of her sons. This was her lived experience as a young Black woman, birthing and raising children and trying her best to save them in a world that seemingly did not see them.

I choose to be a pediatric palliative care specialist so I could stand in the gap for seriously ill children and parents facing the prospect of loss while trying their best to keep living. At my core I believe all families deserve to be cloaked and cared for in the hardest of circumstances, with hope for survival and the best outcome possible that is not dictated by their race, culture, family make-up or financial status, but rather by their humanity. This belief is what fuels me on in my work as I care for patients at the bedside, lead the pediatric palliative care program at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, and advocate regionally and nationally for equitable access to high-quality pediatric palliative and hospice care. In the wake of George Floyd’s Death and the COVID-19 Pandemic, I envisioned a project aimed at deepening our understanding of how Black and Indigenous children and families facing serious illness experience racism in healthcare and how palliative care approaches can be used as tools in anti-racism. In 2021, I was awarded a Sojourns Leadership Award to undertake this work, which will culminate in recommendations for how healthcare workers, hospital systems, and law makers can address the injustices of racism in pediatric serious illness.

My work as a Sojourns scholar will inform not only how we care for Black and Indigenous children and families who need this essential care, but how we think about justice in healthcare for all families, no matter their lived experience. We are currently organizing focus groups of African American and Native American patients and parents living with serious illness who are willing to share their stories about how they have experienced racism in healthcare. These group discussions will help to center their experiences and guide us in our recommendations to the field. Please consider participating in our groups or sharing the information with patients and families you know who may be interested in sharing their story. (see further information below and attached flyer).

On this Juneteenth, I am pausing to reflect on the meaning of freedom and what my mother sacrificed so I can now walk in my own freedom and take part in the liberation of others. As I see it, an essential part of freedom is the ability to live as well as possible for as long as possible even at the beginning of life…despite illness, the color of your skin, or the realities you are born into. I am honored to be called to do the work that I do. I am honored to dedicate my life to standing in the gap.

Theme: Pediatric palliative care benefits

I sat in a sea of clinical paperwork last Sunday and felt like myself for the first time in weeks. I was searching for the order form for Colson’s adaptive stroller, which listed all of its component parts and sizes. Colson’s amazing occupational therapist from his baby days in early intervention was coming to our house the next morning to pick up his big-boy blue adaptive stroller and his awesome green stander with the spaceship motif, and I wanted her to know what she was getting. After researching options to donate this precious, life-giving equipment for over a year, I realized the only place I wanted it was a) where I knew it would get used and b) with an organization that had served us and Colson well. The only way to mitigate the heartbreak of parting from things that belonged to him is to make sure they go to families that will benefit from them. In this way, his generous spirit lives on.

Colson’s early intervention provider was the absolute best fit. His equipment is small because he was always small. Parents must manage a difficult calculus when their little kids need adaptive equipment, given its astronomical cost; the tendency of insurance to drag its feet on coverage; and the changing nature of the needs of complex kids as they grow. Colson’s equipment will now be free “loaner” equipment for other very young kids, while their families figure out what equipment will best serve their needs long term.

Colson’s early intervention provider was the absolute best fit. His equipment is small because he was always small. Parents must manage a difficult calculus when their little kids need adaptive equipment, given its astronomical cost; the tendency of insurance to drag its feet on coverage; and the changing nature of the needs of complex kids as they grow. Colson’s equipment will now be free “loaner” equipment for other very young kids, while their families figure out what equipment will best serve their needs long term.

As I waded through the clinical documentation looking for the stroller details, I felt a familiar mix of pride and sadness. Pride that Jacob and I had managed so much complexity for as long as we did, with as much love as we did, and sadness that we had to. I didn’t keep every document from Colson’s care. Between early intervention, his pediatrician, several inpatient stays, 12 outpatient clinics, the school district, and our state’s Division of Developmental Disabilities and Long-Term Care programs, the amount of paperwork would have reached the ceiling. But I did keep three boxes of things that felt important: clinic reports from his neurology and biochemical genetics teams; progress notes from occupational and physical therapy; medication manuals and hastily scribbled notes from my conversations with various team members, with my questions and their answers tracked in a cryptic shorthand that only I can decipher.

As I looked through it all, I felt my medical mama gears clicking into place again. The almost trance-like linking of my brain, my body, and my spirit working to form a coherent perspective of what is it I’m looking at? What is it we’re dealing with? How am I supposed to manage the unmanageable?

I thought, in particular, of the difficult dance my husband and I did with a seizure medication during Colson’s life. One of the potential side effects of this medication was peripheral vision loss. When we started giving Colson this medication, we were already concerned that he was having difficulty with his vision, and agonized about making it worse. Do we try to spare the eyes, or save the brain? We were constantly trying to solve these ridiculous riddles. There was never a clear answer.

Looking at Colson’s life with a bit of distance now, I wish we had done one thing differently. I wish we had treated our relationship with his palliative care team with the same level of urgency we treated our relationship with his medical home team. Specifically – we had a 6 month follow-up with his medical home team without fail. I knew which clinics I could push out by a few months or more – but felt a sense of duty to check in with his medical home at the cadence they recommended, because they were looking at him so comprehensively. I wish we had done that with palliative care, which we engaged frequently, but on a more ad hoc basis.

I wish we had done this so that someone could have looked at our caregiving duties more comprehensively, and guided us through some of the constant sense-making that we got used to doing instinctively, but not necessarily strategically. I don’t know that it would have changed any of our decisions, but it might have made us re-evaluate them more frequently and find areas where we could adapt our approach and ease the burden on ourselves and Colson. Our competence, at times, felt like a curse. We were almost too good at dealing with the onslaught of information we were constantly absorbing. My boxes of records bear that out.

I wish we had done this so that someone could have looked at our caregiving duties more comprehensively, and guided us through some of the constant sense-making that we got used to doing instinctively, but not necessarily strategically. I don’t know that it would have changed any of our decisions, but it might have made us re-evaluate them more frequently and find areas where we could adapt our approach and ease the burden on ourselves and Colson. Our competence, at times, felt like a curse. We were almost too good at dealing with the onslaught of information we were constantly absorbing. My boxes of records bear that out.

I know that palliative care providers truly mean it when they tell families to connect with them at any time. But it’s an oversimplification to recommend that palliative care providers and caregivers simply make those connection points more consistently and intentionally. I don’t know what the solution is. I do know it’s almost impossible to ask for help, call a care conference, or even think about making changes to a semi-functional care plan when you’re just trying to get your kid through each day safely. So I end this post with a question, and an invitation for your input: what would be most helpful for you, either as a parent or a provider, to ensure palliative care conversations occur consistently during a child’s life, and not just near times of intervention or crisis?

If you have thoughts, please email them to connect@courageousparentsnetwork.org and I will follow-up on this topic in next month’s post. Until then – I wish you peace and strength in your journey.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Liz Morris loves exploring complex questions. Her professional experiences in project management, librarianship, and community development prepared her well for her favorite role as mom to Colson. Colson, impacted by mitochondrial disease since birth, inspired Liz to face the complicated aspects of his life through writing and advocacy. Liz serves as a family advisor at Seattle Children’s Hospital, and is a volunteer ambassador for the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation. She is committed to helping families find the information they need to help them live well in the face of life-limiting illness. You can find Liz on Instagram @mrsliz.morris

Theme: Pediatric palliative care benefits

Have you ever picked up an object in your house and thought, what would I do without this thing? It makes my life easier and better every time I use it. I’ve bought kitchen gadgets on a whim. My favorite is this oversized glass measuring cup; it holds 8 cups and I adore it. I love the handle and its spout. I use it when I make cake batter, stock for my chicken soup, or to pour Jello into fancy little cups. I know if this glass miracle ever breaks, I’ll need another one immediately. I have another gadget that chops up ground beef perfectly. When my sister gave it to me and said it was life changing, I thought, well I’ll decide that and it’s too gimmicky. Now I’m a total evangelist and I buy this tool and hand it out, spreading the word about its goodness. I’ll spare you my favorite painting tools and how they will improve your existence for another blog. You get the picture. There are things in your life that when you are handed or discover them, you just don’t realize how much you now suddenly need them forever after.

That’s what palliative care is to me. This kind of care was a concept I never knew about, nor understood, nor chose, but thank God it was gifted to my daughter and my family. Once it was handed to us, it was life changing.

I attended a seminar with the author and professor Maria Kafalas. She considers palliative care the Marie Kondo of her daughter’s diagnosis. If you don’t recognize her name, Marie Kondo is a professional organizer with a cult following. The premise of the Kondo theory is that the objects you keep should be minimal, and your possessions should reflect only those things that you truly need and that spark joy. Maria’s analogy is so perfect.

Palliative care clarifies and organizes care for your child, even amidst living with a life-altering diagnosis. Kids with critical illnesses truly need palliative care. Our palliative care doctor is one of my favorite humans, and was the spark of our joy on so many days.

Our daughter Lauren was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer at age 7. We went for an appointment with our pediatrician to address Lauren’s aching stomach, and 5 hours later, we met with her chief oncologist. Her stomachache was diagnosed as rhabdomyosarcoma.

Throughout Lauren’s treatment, our palliative doctor and our palliative team became our lifeline. They took time to learn about Lauren, our family, and what was important to us. They knew how being at school made Lauren feel normal again, like her pre-cancer self. They knew she loved the Chicago Blackhawks and might (did) secretly judge you on your ability or lack thereof, to talk hockey or Chicago sports. They knew she had a new puppy, and that she described its breeding as half lab and half bad decision maker. One afternoon in the oncology clinic, Lauren and our palliative team discovered something about families. They came to the realization that you are either a Cocoa Krispies family, or a Cocoa Puffs one, but you shouldn’t be both. We are, and forever will be, a Cocoa Krispies family.

Our palliative team spoke “Lauren” when our oncology team wasn’t fluent. They helped us address the physical pain Lauren was in. They gave us medications and tools to make that pain bearable, and eventually, livable, to the point where Lauren could go to school most days, even after a morning of chemo. Our palliative team introduced us to pediatric psychologists and psychiatrists to help with the emotional pain inextricably linked with a hard diagnosis. As Lauren’s oncologists worked on solving for tomorrow, her palliative care team worked on solving for today.

On very hard days, Lauren would tell me that her big worries were back. That meant she was worried about dying. The open and honest relationship that bonded us to our palliative team allowed and encouraged me to share Lauren’s big worries with them. Their words and comfort brought some respite to those hard days.

On very hard days, Lauren would tell me that her big worries were back. That meant she was worried about dying. The open and honest relationship that bonded us to our palliative team allowed and encouraged me to share Lauren’s big worries with them. Their words and comfort brought some respite to those hard days.

When the promise of more tomorrows was fading, our palliative team helped us make decisions about what Lauren wanted to accomplish and how we wanted her last days with us to look. Our most difficult and important conversations with Lauren and all of our children were at the encouragement of our palliative team. My husband and I would never have found the strength nor recognized those opportunities and moments without the support and confidence they instilled in us. I will be eternally grateful for those talks.

If you are reading this and going through some hard days, I’m so sorry. If you and your child have big worries, I’m so sorry. If the promise of tomorrow seems like a mirage, I’m so sorry. Please ask for palliative care. Ask at the start of the diagnosis, the middle, or near the end. Please ask. You’ll find respite, support, and exactly the thing you didn’t know you needed.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Amy Graver currently works in the corporate world, and is a writer, a wife, and mom of four. Her daughter Lauren was diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma at age 7. Amy’s writing chronicles the journey on which cancer has taken her family. Lauren’s cancer diagnosis imposed a new reality and a new perspective on life. She is dedicated to making the cancer experience better for future families. Amy is an enthusiast of US presidential history, she aspires to be a professional seashell collector, and is absurdly competitive about things that don’t matter.

Theme: Pediatric palliative care benefits

I am a pediatric psychologist who works with children with life threatening illnesses and their families. When my 3-year-old daughter Molly was diagnosed with cancer in April 2020, some of the first people I told were my colleagues on the pediatric palliative care team. During the next few days, the conversations were more typical of those I was having with my other friends – tangible offers of support for myself and my hospitalized child as well as for my husband and child at home, gifts being delivered to the house and messages of hope. Because many of them were also working at the hospital, there were small things that outside friends could not provide, such as leaving coffee and breakfast outside the hospital room, but the sentiment was the same – we are here, how can we help, we got this.

I am a pediatric psychologist who works with children with life threatening illnesses and their families. When my 3-year-old daughter Molly was diagnosed with cancer in April 2020, some of the first people I told were my colleagues on the pediatric palliative care team. During the next few days, the conversations were more typical of those I was having with my other friends – tangible offers of support for myself and my hospitalized child as well as for my husband and child at home, gifts being delivered to the house and messages of hope. Because many of them were also working at the hospital, there were small things that outside friends could not provide, such as leaving coffee and breakfast outside the hospital room, but the sentiment was the same – we are here, how can we help, we got this.

However, around day five, a second type of cancer was found and Molly went from being a standard risk leukemia patient with a very good prognosis to a huge question mark in terms of a plan for treatment and what her life would look like as a result. As the oncology team worked around the clock to elicit opinions from the worldwide pediatric oncology community and develop a treatment plan, I began to send my palliative care colleagues more questions about what this proposed treatment would look like for my child and my family. On the day that we received the final pathology report definitively showing my child had two separate cancers, I requested that a formal palliative care consultation be placed.

Over the past 15 months, my colleagues on the pediatric palliative care team have been a huge part of Molly’s care. As I reflect back on my experience, I am struck by two pervasive themes. First, what my initial reasons were for getting this team involved and how this has played out. And second, the numerous additional benefits that I had not anticipated. At this point I think it is important to acknowledge that I came into this experience with a strong bias about the benefit of early palliative care involvement and also a knowledge of palliative care that is not typical of most parents in my situation. I have spent my career as a pediatric psychologist collaborating with palliative care teams and being mentored by palliative care researchers. Prior to Molly’s illness the palliative care team covered a small portion of my salary and I was an active member of their team. Perhaps most importantly, I did not equate palliative care involvement to mean my child was terminal or was approaching the end of her life.

My Initial Reasons for Involving Palliative care at the Outset

As information about the treatment plan started being conveyed, my biggest concern was around symptom management. The treatment plan the team was proposing was completely unique to Molly. While each individual drug had been used as part of standard protocols and had an established side-effect profile, the combination of drugs had not and therefore the potential side-effects and the severity of side-effects was completely unknown. This was terrifying. If there was no experience using these combinations of drugs, then I wanted a proactive plan for symptom management. And I knew that this was an area in which palliative care clinicians are second to none.

Not only was I worried about the acute symptoms (nausea, mouth sores, nerve pain, etc.) I was also worried about Molly’s quality of life. At this point no one had any idea about her prognosis or how long her life may be. So while the intent of treatment was curative, I was also very mindful (although unable to articulate at the time) that I wanted her time to be high quality. I wanted her to be able to get home and be able to play with her twin sister. I wanted her to be able to play outside without worrying about pain. I wanted her to learn to swim.

Over the course of the next few days, the palliative care team helped me articulate these goals. Once established, they took action. Because there was no standardized symptom management plan, it seemed that they had more leeway to think outside the box and try medications that were not part of the standard protocol. Olanzapine, which was started to proactively prevent nausea, was a game changer for her and she made it through six rounds of chemo with pretty minimal nausea.

After the treatment plan was established, the palliative care team also helped my husband and I understand what would be coming, and again, make proactive decisions that would hopefully give her the best possible quality of life. At their suggestion, we requested a g-tube be placed after she had recovered from her first round of chemotherapy. Not only did this take a significant amount of stress off us around medication administration, it was crucial during her stem-cell transplant, where she would have likely lost an NG daily from throwing up.

Unanticipated Benefits

Over the past year the palliative care team has continued to be an invaluable member of Molly’s very large care team, for the reasons discussed above, but also for reasons that I did not initially consider. During the 220 days that my daughter spent in the hospital, the palliative care nurse practitioner, Missy, was her most consistent provider. While the attendings, residents, and my husband and I switched in and out of the hospital Missy was able to reflect back over the past days or weeks or months in a way that no one else could, providing a longitudinal perspective that felt critical. During our 70+ day hospitalization for transplant, as the days and weeks blended together, I remember struggling to answer a simple question about if she looked better or worse than she had the week before, because I just had no idea. Missy recognized my distress and jumped in, providing with some basic scaffolding and with her help I was able to articulate that she was actually looking much worse, and immediate changes were initiated.

Over the past year the palliative care team has continued to be an invaluable member of Molly’s very large care team, for the reasons discussed above, but also for reasons that I did not initially consider. During the 220 days that my daughter spent in the hospital, the palliative care nurse practitioner, Missy, was her most consistent provider. While the attendings, residents, and my husband and I switched in and out of the hospital Missy was able to reflect back over the past days or weeks or months in a way that no one else could, providing a longitudinal perspective that felt critical. During our 70+ day hospitalization for transplant, as the days and weeks blended together, I remember struggling to answer a simple question about if she looked better or worse than she had the week before, because I just had no idea. Missy recognized my distress and jumped in, providing with some basic scaffolding and with her help I was able to articulate that she was actually looking much worse, and immediate changes were initiated.

Missy’s consistency helped our family in many other ways. The relationship she developed with Molly was one based on trust and play. When Molly was not feeling well and refusing to participate in an exam by any of the doctors or nurses, she would open her mouth for Missy. And despite developing significant separation anxiety during her prolonged hospitalization, Molly would often agree to having a playdate with Missy, allowing her very tired mom to not only go to the cafeteria to buy a cup of coffee, but also to drink it while it was hot.

Reflection

In my clinical work prior to Molly’s diagnosis, I cannot count how often I have heard providers make statements along the lines of “This family isn’t ready for a palliative care consult” or “We don’t want this family to think their child is dying” when talking about why a palliative care referral has not been placed. While I found these statements annoying before Molly’s diagnosis, thinking about them now – from the vantage point of a parent — makes me irate, because I know how much my child and our family benefited from early palliative care involvement. These types of statements perpetuate the myth that palliative care is for dying patients. And while this may be true in adult medicine, it is certainly not the case in pediatrics. Early palliative care allowed for Molly’s treatment to have a dual focus – on cure AND on quality of life. Never once did Molly’s oncology question my wish for palliative care involvement. In fact, they welcomed it. While this could have been because of my role on the palliative care team, I think it was because they too recognized the high degree of uncertainty inherent in the dual diagnoses. Over the past 15 months the two teams have done an incredible job of working together to provide the best possible treatment for my daughter. Molly still had many side-effects from her extremely intensive therapy. But she also had a plan in place to address these side effects, in a way that would allow her to have the best possible quality of life. And for this, I will always be incredibly grateful.

In my clinical work prior to Molly’s diagnosis, I cannot count how often I have heard providers make statements along the lines of “This family isn’t ready for a palliative care consult” or “We don’t want this family to think their child is dying” when talking about why a palliative care referral has not been placed. While I found these statements annoying before Molly’s diagnosis, thinking about them now – from the vantage point of a parent — makes me irate, because I know how much my child and our family benefited from early palliative care involvement. These types of statements perpetuate the myth that palliative care is for dying patients. And while this may be true in adult medicine, it is certainly not the case in pediatrics. Early palliative care allowed for Molly’s treatment to have a dual focus – on cure AND on quality of life. Never once did Molly’s oncology question my wish for palliative care involvement. In fact, they welcomed it. While this could have been because of my role on the palliative care team, I think it was because they too recognized the high degree of uncertainty inherent in the dual diagnoses. Over the past 15 months the two teams have done an incredible job of working together to provide the best possible treatment for my daughter. Molly still had many side-effects from her extremely intensive therapy. But she also had a plan in place to address these side effects, in a way that would allow her to have the best possible quality of life. And for this, I will always be incredibly grateful.

Theme: Pediatric palliative care benefits

When my son was just over one month old, my husband and I went on a date. It was a rainy November day in 2016, and we were determined to leave the house together to do something, anything, not related to baby duty. Of course, as a new mom whose infant son had just spent a harrowing week at the local children’s hospital and been diagnosed with mitochondrial disease, it was hard to tear myself away. But, in our visit to a local art studio, I found a piece of inspiration that informed my parenting journey profoundly, and helped me embrace palliative care early in my son’s life. A beautiful drawing of a pair of hands, lifting up a heart with wings, and a quote:

“May I always know hope

Balance action with acceptance

Find the grace in every moment

Showing compassion

As I love without holding back”

This simple poem, prayer, koan became my mission statement for living a purposeful and peaceful life with my son. For feeling, in some small way, that I could shape the gutting actuality of his disease into an exuberant existence. I’d like to say that when his neurologist first recommended that my husband and I meet with our hospital’s Pediatric Advanced Care Team (PACT), I immediately tapped into these guiding words and scheduled that meeting with a smile on my face. Of course, that’s not what happened, but this idea of balancing “action with acceptance” helped me get to that place much sooner than I may otherwise have.

My son’s neurologist recommended we pursue conversations about palliative care when, at about seven months old, my son’s seizures had not come under control of medication despite multiple attempts. I immediately bristled at the suggestion to meet with the PACT, and sharply asked “Aren’t those the people who help with things like advanced directives?” I was in raging denial that we might need to deal with something like that, so soon in our son’s life. The doctor gently explained that yes, advanced directives are included in the PACT scope of work, but so were many other things related to helping our son live a comfortable life, and helping us as parents feel in control of our decisions related to his care. I cannot overstate how powerful it was to have a doctor explain her palliative care referral in a way that positioned it as an opportunity for influence, rather than a form of resignation.

Since that time, my husband and I have met with the Pediatric Advanced Care Team twice. The first time, when our son was about eight months old, was a simple “get to know you” conversation. We were able to share more about our son’s incredible personality, his primary diagnosis, his constellation of symptoms, and our hopes, fears, and values for our family. The PACT representatives explained the many ways they could help us, such as accompanying us to clinic visits, facilitating complex decisions about our son’s care with us and his army of medical providers, serving as a sounding board for me and my husband, or making referrals to outside community agencies for respite or other support. I realized the important differentiating factor between them and our son’s doctors: our son’s doctors are (rightly) focused on the physical manifestations of his disease. The palliative care providers help us focus on all the other ways those manifestations impact his, and our, lives – in our heads, in our hearts, in our home.

Our second meeting was more recently, just this past December, as we prepared for our son’s G-tube surgery. My husband and I both felt strongly that placing a G-tube was the right thing to do, but we wanted to be on the same page about why we felt that way. So, we went to our meeting with the PACT armed with the following discussion topics (and influenced by the CPN Framework for Difficult Decisions):

- Why does this intervention feel appropriate at this time? Under what circumstances would we stop using this intervention?

- Assuming all things remain the same – what would happen if we stopped using his G-tube and his ‘failure to thrive’ went untreated?

- What are other potential interventions or medical decisions that we might need to consider in the future? How do we feel about them currently?

As a result of this conversation, my husband and I came away with some insights into the value of palliative care that I hope may be useful for others considering incorporating it into their child’s life.

- For us, palliative care is not a plan. It’s a philosophy. There are far too many medical and developmental variables related to our son’s condition for us to do any concrete scenario planning. But, by naming our priorities and our uncertainties with the PACT, we can co-create mutual understanding that ultimately serves our son. The PACT learns about our family’s values and priorities, while my husband and I learn about caretaking options we may not otherwise have been aware of. In our most recent discussion, we learned more about what comfort feeding is. We also learned about some medical circumstances where short term vs. long term invasive interventions may be relevant, and were in a safe space to talk about our feelings related to that.

- Perhaps most critically, palliative care providers help families hold an incredibly intricate space. When your child has a life-limiting illness, there are no easy conversations about their futures, and there are no right answers. Every situation is deeply unique. These are not issues we want to discuss with family and friends, largely because they are private, but also because we want loved ones to be able to engage with our son, not his disease. We have been fortunate that, thus far in our son’s life, we have not had to make any quick decisions about his care, nor have we had to make decisions under extreme emotional duress. But the possibility is always there. Understanding that there are people on our team who know us, and him, and can reflect our priorities back to us in challenging or exhausting times is a huge source of comfort.

I was a nervous wreck prior to our son’s G-tube surgery, but on the actual day, I found myself full of calm. In that beautiful space between action and acceptance. I knew we had thought through our decision as fully as possible. This allowed me to release lingering feelings of anxiety and self-recrimination, and be fully present for my son during his recent procedure and current recovery. This capacity for presence, aided by palliative care, is invaluable to me as a mom, who, fifteen months into my son’s life, marvels at his beauty, strength, and potential every single day.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Liz Morris loves exploring complex questions. Her professional experiences in project management, librarianship, and community development prepared her well for her favorite role as mom to Colson. Colson, impacted by mitochondrial disease since birth, inspired Liz to face the complicated aspects of his life through writing and advocacy. Liz serves as a family advisor at Seattle Children’s Hospital, and is a volunteer ambassador for the United Mitochondrial Disease Foundation. She is committed to helping families find the information they need to help them live well in the face of life-limiting illness. You can find Liz on Instagram @mrsliz.morris

Theme: Pediatric palliative care benefits

Summary of survey results published in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management

Jackelyn Y. Boyden, PhD, MPH, RN; Mary Ersek, PhD, RN, FPCN; Janet A. Deatrick, PhD, RN, FAAN; Kimberley Widger, PhD, RN, CHPCN(C); Gwenn LaRagione, BSN, RN, CCM, CHPPN; Blyth Lord, EdM; Chris Feudtner, MD, PhD, MPH

Introduction

Courageous Parents Network is proud to work with provider-researchers who are investigating issues and questions common to the lived experience of families caring for very sick children. This study, published in the July 2020 Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, is an inquiry into what pediatric palliative care services (PPC) families caring for children at home most value. For the study, the investigators recruited CPN and other families in the U.S. to better understand how they prioritize a wide range of palliative and hospice services. This is a non-technical description of the study and results. For more in-depth information, read the published article.

The study

More and more children with life-limiting illness and complex care needs are being cared for by their families at home, particularly toward end of life. They and their families are supported by a range of palliative and hospice services and providers. Because the resources are limited, or finite, it is important for the medical community, advocates and government agencies to effectively allocate what is available. Understanding what the primary caregivers, mainly families, value should be an important factor in guiding these decisions. Families’ values can also be an indicator of where care needs improvement.

A team of researchers set out to investigate family priorities in a recent study of parents recruited from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Pediatric Advanced Care Team (PACT), as well as from Courageous Parents Network (CPN), using the CPN newsletter and social media to invite participation. All of those who responded were screened and provided electronic informed consent. They completed a survey via a Web link, either together with the researchers or independently. Participants were compensated with a gift card for their time and effort.

The families

Forty-seven parents from 45 families participated in the study. Most participants were mothers, who were white, non-Hispanic, married or partnered, and had completed college or graduate school. About one-third (30%) of participants were bereaved and many (70.2%) were caring for their child at home during the study. 34% received care for their child from CHOP; the other 66% were CPN families who received care from providers across the United States.

The participants were parents to 45 children who have received pediatric palliative care. Approximately half of the children were 0-9 years, and half were 10-25 years. The most prevalent diagnoses included neuromuscular, neurologic, or mitochondrial (51.1%), genetic or congenital (48.9%), cardiovascular (22.2%), and metabolic (22.2%) diseases.

Study design

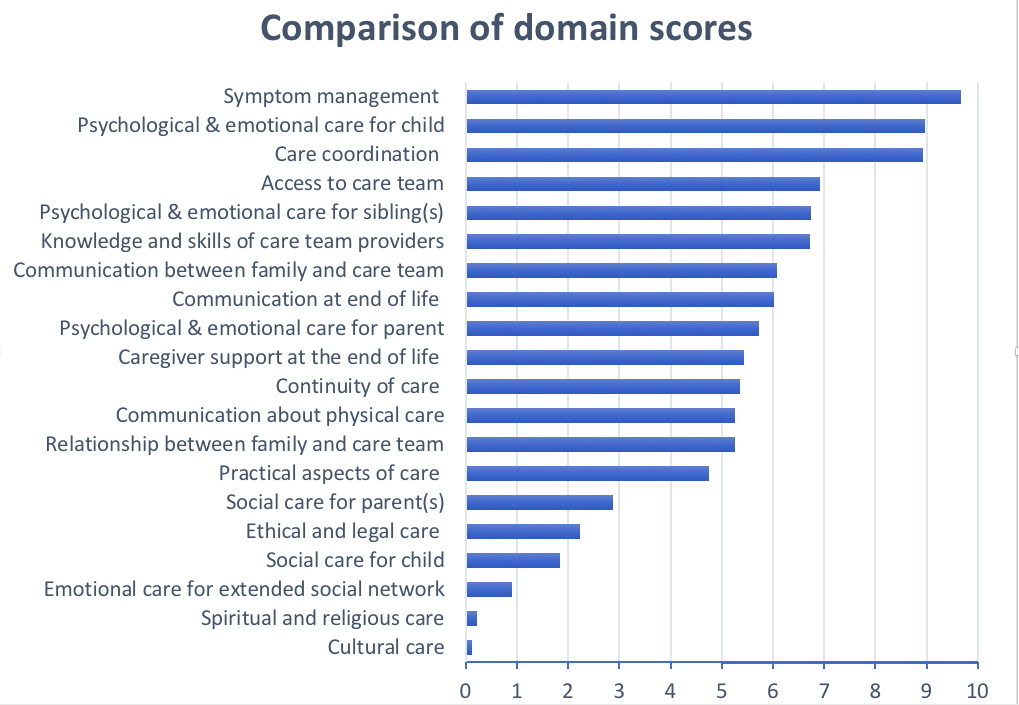

The participants received a list of 20 “domains,” or features, of high-quality pediatric palliative and hospice care in the home. This list covered a wide range of services provided by PPC and hospice providers. All participants were given definitions of the domains to ensure that everyone surveyed had the same understanding of what was intended. They were presented with different combinations of the 20 domains; each time, they were given 4 domains and asked to choose the domain that they felt was the most important in supporting their child in the home, and the one they felt was least important. Then, using statistical analysis, the researchers calculated scores for each of the domains. The domains were then placed on a scale, from most important to least important, to represent how the domains ranked (or compared) in importance to each other. For example, a domain with a score of 10 was considered by participants as twice as important as a domain with a score of 5. The full list of domains and their definitions is included in the article.

Results

Parents ranked the domains Symptom management the highest, followed by Psychological & emotional aspects of care for the child, and Care coordination. Among the lowest-ranked domains were Emotional care for the family’s extended social network, Spiritual and religious care, and Cultural care.

The results differed somewhat based on different groups of families. For example, parents with other children rated the domain Psychological & emotional care for the sibling(s) as a higher priority, and in fact twice as important, than did families without other children. Bereaved parents rated the Caregiver support at the end of life domain as more important than did families currently caring for their child, and not necessarily facing end-of-life issues. There were no significant differences between the scores of the 44 mothers and the three fathers who participated in the study.

Conclusion

In their report, they also noted four limitations of the study:

- The demographic characteristics of the participants were relatively similar. Additional research with larger and more diverse samples is recommended, so that we can more fully understand parental priorities, particularly among underrepresented groups.

- The study did not collect data on the actual programs families receive or that are available. As a result, parents may have evaluated a domain as less important if the services addressing the domain were ineffective or unavailable, or if families chose not to use them.

- Although the domains were based on NCP Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care and informed by PPC-specific guidelines and a panel of PPC stakeholders, the study may have left out important domains.

- The study does not address how much the rankings might change over time for families; for this, studies that follow families over time are needed.

Nevertheless, the researchers believe that these results present important directional feedback for future conversations about prioritizing finite resources and focusing care improvement efforts.

This infographic is another way to read the findings: PediatricPalliativeatHome_Study_Infographic_2021-01-05

Thank you

Many thanks to the CPN parents who participated in this study! If you are interested in contributing your knowledge and experience to future efforts, please watch your CPN newsletter and be certain to follow CPN on Facebook and LinkedIn.

Additional Note

The researchers are currently working on developing a questionnaire to help measure how families experience these domains of palliative and hospice care at home. The goal of this questionnaire is for families to provide real-time (that is, at the time they are receiving care) feedback to their providers, so providers can work together with families to make sure that the care they receive is meeting their needs. The first phase of this development project included the same CPN and CHOP families mentioned in the summary above, who also helped prioritize items to include on this questionnaire (published article coming soon).

In the second phase of this project, beginning in January 2021, they will be working with families currently caring for their children at home, as well as with palliative care and hospice providers, on making this questionnaire more useful for families and for providers. If you are interested in helping out with this next project, please keep an eye on our CPN newsletter and social media pages for more details that will be coming out soon. This is how we families make it better for those that follow.

Theme: Pediatric palliative care benefits

In this Zoom interview with CPN, Michelle — mother of Alex (age 7) and Julianna, who was diagnosed with a severe form of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease — articulates how palliative care helped her specifically. The care conference at the last hospitalization, the conversation about trach and trajectory, and hospice.

Theme: Pediatric palliative care benefits

The mother of a boy with severe neurological impairment talks about how her son’s palliative care doctor shared what she anticipated would happen when his body eventually (and slowly) shuts down. The mom then describes what it did look like – the first indication – and how she was thus prepared. “This helped me when the end of his journey did come.”

Theme: Pediatric palliative care benefits

A pediatric palliative care doctor who specializes in children with severe neurological impairment talks about how palliative care specialists help parents take a step back, including about baseline, without jeopardizing the continuing treatment being delivered by the child’s specialists.

Theme: Pediatric palliative care benefits

Our daughter, Blair, was born with a progressive terminal disease called Sanfilippo Syndrome. When she was diagnosed at age six, our pediatrician mentioned palliative care and hospice to us. We really didn’t think it applied to us since she was not near the end of her life. Fortunately, a mom in the Sanfilippo Syndrome community explained to me the benefit of having palliative care on board BEFORE my daughter was too progressed. She suggested that it would be beneficial for the doctor to get to know Blair and our family early in the process. That way we could establish a relationship with him and he would be able to better guide us through the process when it was time. We could not be more thankful for that advice.

For several years, we met with the palliative care doctor only a few times a year for him to simply check in with us on Blair’s health. Over time he began to touch on topics that we would need to think about and be prepared for as our daughter progressed. The office provided a safe place for us to discuss extremely difficult decisions like signing a Do Not Resuscitate form. Our doctor and his team listened carefully, authenticated our feelings, and supported our decisions.

We were thankful to have established this relationship when Blair was diagnosed with gallstones and her gall bladder needed to be removed. It is extremely risky for a fifteen year old with Sanfilippo Syndrome to have anesthesia. Our palliative care team was able to schedule a meeting for us with Blair’s surgeon, neurologist, geneticist and gastroenterologist in order to make the best decision for her. This meeting helped give us confidence in our decision to go through with the surgery. It would have been highly unlikely we could have coordinated such a meeting without the support of palliative care.

During the last four months of Blair’s life, she had very complicated symptoms of discomfort that were extremely difficult to diagnose. She was having uncontrollable movements most of the day, large amounts of secretions, extreme weakness, and feeding difficulties. We rarely changed her out of her nightgown to try to keep her as comfortable as possible. She would have been miserable if she had to be taken anywhere in the car or in her wheelchair since she would either be moving uncontrollably, flopped over due to the weakness, or choking on secretions. Palliative care really became invaluable to our family at this point. Rather than transport Blair around to several doctors’ appointments to figure out what was going on and how to help her, our doctor began coordinating all of her care. He came to our home to check on her and reached out as needed to her specialists. We could call the doctor around the clock as needed, and trust me we did. The doctor was always calm and supportive no matter what time we called.

The palliative care coordinator checked in with us regularly during those months. She would often ask what could be done to help us. After several conversations, she picked up on our lack of sleep and offered to help get us nursing at night. Our insurance company had never approved nursing, but she somehow got it approved. She was so helpful, and even understood when I couldn’t get comfortable with hiring a night nurse for Blair. She just continued to support us.

About a month before Blair passed away, the palliative care team came to our house and we all agreed that it was time to bring in hospice. Palliative care coordinated all of Blair’s hospice care making the transition seamless. Since Sanfilippo Syndrome is so rare, it is doubtful the hospice doctor would have ever had a patient with it and with all the stress we were under it would have been difficult to deal with a new doctor. We received all the benefits of hospice care while still having palliative care. That also meant there were fewer new people in our home and that this doctor that we had spent years forming a relationship with would be by our side at the end of Blair’s life.

Thinking about our relationship with the palliative care team truly brings tears to my eyes. They knew us so well and we trusted them fully to help guide us through the process. They prepared us along they way with baby steps and never judged us on our decisions. Instead, they were both supportive and encouraging regarding our care for Blair. They cared deeply for our daughter as well as the rest of the family. We could not be more thankful that our children’s hospital has such a wonderful palliative care team. We cannot imagine going through that difficult time without them.