-

![“I really appreciated the child-life specialist who guided us [through end-of-life for our older son.]”](https://img.youtube.com/vi/VI4wyRe9SLY/maxresdefault.jpg)

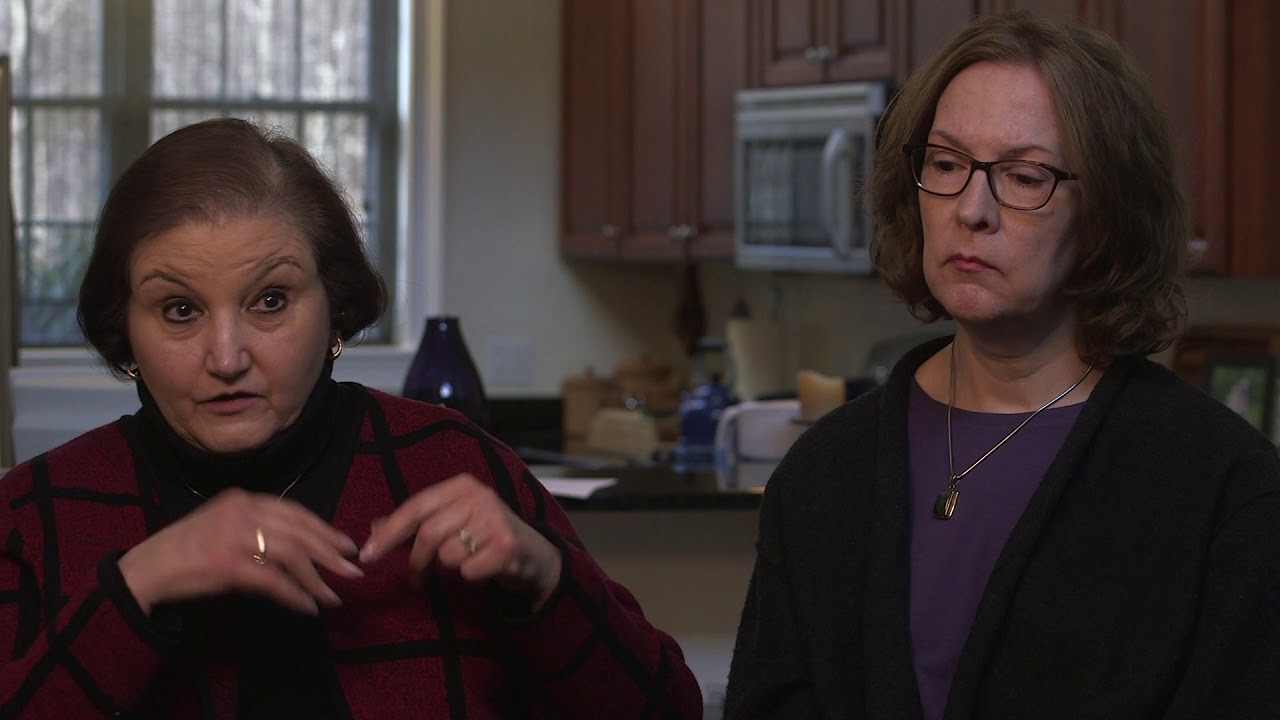

“I really appreciated the child-life s...

-

Communicating with the siblings: What ca...

-

As parents, we can dose ourselves with t...

-

Emotion in front of the children: The ru...

-

Illness and Loss: What is mentionable is...

-

Educating others to talk openly and hone...

-

A pediatric palliative care social worke...

-

Siblings: “I wracked my brain about ho...

-

Siblings: Holding on to hope while also ...

-

She, the sister, finally understood. She...

-

Transitioning to End of Life: Helping ea...

-

Talking to siblings about end of life.

SHARE

Videos

Theme: Siblings at End of Life

“I really appreciated the child-life specialist who guided us [through end-of-life for our older son.]”

Page: 1 of 2

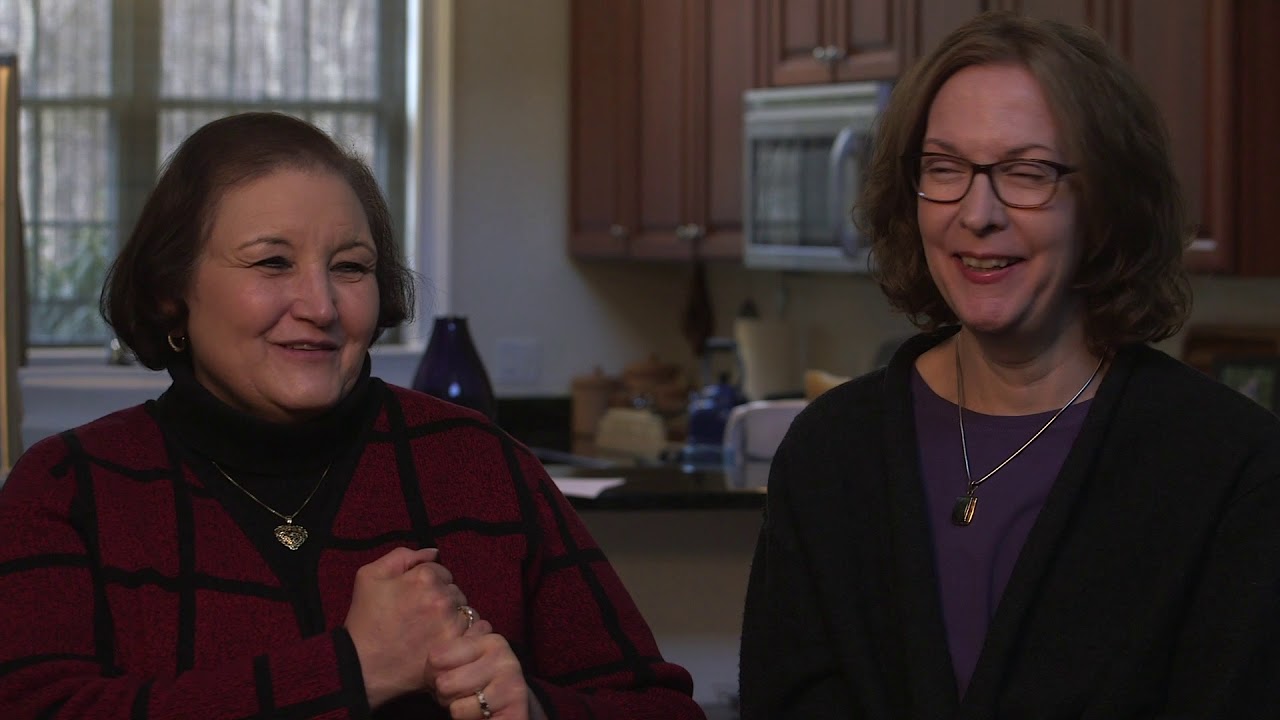

![“I really appreciated the child-life specialist who guided us [through end-of-life for our older son.]”](https://img.youtube.com/vi/VI4wyRe9SLY/maxresdefault.jpg)

“I really appreciated the child-life specialist who guided us [through end-of-life for our older son.]”

SHARE