Theme: Feeding Tubes

“I’m so glad I have a sister. Otherwise, it would just be me, you, Daddy and Suki (our dog).” Those were the words spoken to me recently by my four-year-old daughter, Nika as I rounded the corner from Sasha’s sit to stand recliner and headed towards the hall. I was stunned but tried not to show it. It had been a hard week in the household. I returned from a remarkable caregiver’s workshop in Washington DC to find that Sasha took a swift downturn during my ever so brief absence. We had already taken her to her primary care provider. It was a lengthy visit. As I sat there, the most surreal wave washed over me – a knowledge crest that everything was about to change.

My husband Mike came to the appointment to help get Sasha in and out of our vehicle. We had Nika in tow as the appointment fell on a non-school day. Fortunately, there is a cute park on the clinic’s campus, and the weather cooperated for Nika to play for nearly 2 hours while Sasha and I investigated the next steps in her care plan. I appreciated the levity of Mike sending me time trials as Nika ran laps, “11.77, 12.08, 11.76, 13.31.” Random figures illuminated my phone with no explanation – a pleasant mystery that provided a helpful distraction. The day was a brighter gray than some during a particularly windy October.

appointment fell on a non-school day. Fortunately, there is a cute park on the clinic’s campus, and the weather cooperated for Nika to play for nearly 2 hours while Sasha and I investigated the next steps in her care plan. I appreciated the levity of Mike sending me time trials as Nika ran laps, “11.77, 12.08, 11.76, 13.31.” Random figures illuminated my phone with no explanation – a pleasant mystery that provided a helpful distraction. The day was a brighter gray than some during a particularly windy October.

Daylight savings was coming soon. I sat there silently bemoaning as I waited for Sasha’s PCP to enter the exam room. I’ve always resented the changing of clocks. In my college years, my first taste of adulthood, the time change always took me aback as it collided with an irresponsible modus operandi. Seemingly always in a public establishment, I’d look up only to realize I was an hour off on my given day. Years later, upon having my first child—a daughter with special needs—I would marvel, with frustration, at how deeply her days were affected by adding or taking away even one hour from her already tenuous schedule. Now, in middle age, I resent the changing of clocks for an entirely different reason: who are we to collectively manipulate time? What gives us the societal audacity to control clocks? Do we think we are God? Little did I know—especially in those college years—that time would become such a burden during most of my child-rearing years. I would either wish for it to speed up amid the angst of “When will this ever end?” or to slow down indefinitely so I could cherish the good years.

For nearly two decades, that balancing act came alongside a family unit of 2-3 individuals. While a single Mom to Sasha, there was never a reality of adding a sibling to her chaos. And when I met my second husband as Sasha was approaching age five, I was still a steadfast NO! My hands felt full with an extremely hyperactive child with significant special needs. Being in the throes of destructive sleepless nights, a nocturnal manic state that is common for children with Sanfilippo Syndrome, I knew that adding another child would be the rush of air that pushed down the line of dominos. As Sasha approached nine and we learned of her diagnosis of Sanfilippo Syndrome, we were faced with an unthinkable reality – Sasha’s body carried something fatal. With that realization came the heavy understanding that adding another child would mean they, too, might one day experience a traumatic loss. I doubled down on my steadfast “no” but was that ever the right way to view things? In truth, we could all lose anyone in an instant. Who was I to play God…to try and control any outcome?

My phone continued flashing Nica’s times as I chatted with our PCP’s counterpart, a new nurse practitioner on Sasha’s medical team who was visibly committed to addressing the clinical concerns unfolding. We discussed the preceding week and the cascade of events – Sasha’s sudden struggles with swallowing, her significant weight loss and increased tremors while eating. A swallow study was ordered. I left with numerous instructions, including recommendations for utilizing Sasha’s g-tube for nutrition within a specified framework.

The g-tube. A gut-wrenching decision that I fought so hard against that preceding year. Nine months of meeting with numerous specialties – Palliative, Genetics, Neurology, Complex Care. Messaging friends and acquaintances in the Sanfilippo community. Reaching out to fellow nurse friends to discuss the clinical implications. Listening to interviews of families before me who navigated the same decision. Middle-of-the-night brainstorming sessions filled with self-reflective thoughts. Looking back on the early days post diagnosis. I remembered sitting in Sasha’s cozy bed, holding her close, telling her I would never initiate any invasive procedure. We would let nature guide us and she could tell me when she was ready to be done with the fight. I told her to never hold on for me or anyone else. When she was tired, she could let us know and we would support her decision to let go. I would never play God.

The g-tube. A gut-wrenching decision that I fought so hard against that preceding year. Nine months of meeting with numerous specialties – Palliative, Genetics, Neurology, Complex Care. Messaging friends and acquaintances in the Sanfilippo community. Reaching out to fellow nurse friends to discuss the clinical implications. Listening to interviews of families before me who navigated the same decision. Middle-of-the-night brainstorming sessions filled with self-reflective thoughts. Looking back on the early days post diagnosis. I remembered sitting in Sasha’s cozy bed, holding her close, telling her I would never initiate any invasive procedure. We would let nature guide us and she could tell me when she was ready to be done with the fight. I told her to never hold on for me or anyone else. When she was tired, she could let us know and we would support her decision to let go. I would never play God.

That time now felt so out of reach, so long ago, like she and I were completely different people. I couldn’t believe the day I found myself sitting in a surgeon’s clinic, waiting for a g-tube consultation. He thought Sasha and I were there to schedule the surgery. In reality, I was there to ask the question, “who are we to think we can change course in an agreed upon pact?”

A highly rushed individual, as trauma surgeons will be, he bound through the exam room door and asked even before making eye contact or sitting down, “What questions do you have for me?” I stared as I waited for him to find his seat and scoot over via his three-wheeled black vinyl stool. A lanky fellow with wisps of black hair along a mostly bald scalp, his shoulders too broad for the wash-faded indigo scrubs, I quietly wondered if he was a long-distance runner. He looked at Sasha and saw my reservations. Knowing we were both rushing to get out of there, I spoke rapidly to squeeze it all in. Eventually, he softened and shared a personal story of his own father temporarily needing a g-tube. He could not impress upon me enough, he stated, the importance of nutrition and hydration in all phases of the lifespan. In that moment, he became more than a surgeon. He became human.

I told him I’d think it over and he shared the process for scheduling. It would not be an immediate phone call, I told him. He encouraged me to call and make an appointment, pointing out that as the day approached, I could always cancel if I was still feeling unsure. He left. I felt a bolstering confidence, ever so briefly. I was not reneging on an agreement made to Sasha so many years ago. And I certainly was not playing God. Was I?

“12.65” Nika’s time trials at the clinic’s park were ending alongside our appointment. Mercifully, Nika did not ask what transpired, an unusual occurrence for her inquisitive nature and foreman mindset overseeing all of Sasha’s care needs. She was consumed in exhilaration by her newfound mastery of time. She had learned through her dad’s coaching that she was slowing down ever so slightly each time she approached the finish line. He had explained that if she made a final push as the imaginary line approached, her time would improve.

There will be times in virtually all our lives, where we will be asked to make a decision standing at the crossroads of faith and uncertainty – at the intersection of medicine and personal philosophy. We may be called to decide for ourselves or for a loved one in a way that directly impacts a clinical outcome.

I have been fortunate to have a care team that welcomes these discussions, even discourse when necessary and who recognizes that philosophy is sometimes malleable and that certainty is never a guarantee. In a world that feels unquantifiable, when making decisions that feel impossible, I came to realize that an 80/20 ratio may be the best that I can do. If 80% confidence in a decision can be obtained, then that is where I will hang my hat. Those decisions may evolve with the revelation of new information or the presentation that is in front of you – our minds can change, and that is alright.

I didn’t know what to say in response that day when Nika proclaimed how happy she was to have a sister. I fought back tears and simply offered, “I’m so glad you have a sister too.”

Joanne Huff comes to Courageous Parents Network as a long time follower and parent enthusiast of the organization. As the Mother of two girls, the oldest of whom has the rare disease MPS IIIA/Sanfilippo Syndrome, Joanne has benefited tremendously from the intimate parent interviews and candid, vulnerable story sharing throughout numerous thought provoking blog posts. As her daughter’s activities and lifestyle started to slow down with disease progression, CPN became a larger anchor in times of uncertainty and unrest. It is through this lens that Joanne hopes to share experiences and insights via the CPN blog.

Joanne Huff comes to Courageous Parents Network as a long time follower and parent enthusiast of the organization. As the Mother of two girls, the oldest of whom has the rare disease MPS IIIA/Sanfilippo Syndrome, Joanne has benefited tremendously from the intimate parent interviews and candid, vulnerable story sharing throughout numerous thought provoking blog posts. As her daughter’s activities and lifestyle started to slow down with disease progression, CPN became a larger anchor in times of uncertainty and unrest. It is through this lens that Joanne hopes to share experiences and insights via the CPN blog.

Joanne completed nursing school after her daughter’s diagnosis, receiving her Bachelors of Science in Nursing from Plymouth State University, Plymouth NH. She enjoyed community liaison work with home care providers of adults with special needs up until her own daughter’s care became increasingly more involved. In addition to serving on the Boards of New England Regional Genetics Group (NERGG) and Adaptive Sports Partners through 2024, she has found great purpose in volunteer work advocating for policy improvements and change in Washington DC with the National MPS Society. In her free time, Joanne seeks balance and refuge with yoga, hiking and performing as an ensemble Soprano vocalist with the Pemigewasset Choral Society. When not blogging for CPN, Joanne enjoys sharing offerings on her personal Blog Folding Origami for God. She resides in Bow New Hampshire with her two daughters, Sasha and Nika, her husband Mike and her yellow lab Suki.

Theme: Feeding Tubes

Eighteen years ago, my world was turned upside down when my daughter, Waverly, was diagnosed with Sanfilippo Syndrome. One month later, my son, Oliver, was given the same diagnosis. My family was living in London, embarking on a new career adventure when everything we had planned was no more.

Eighteen years ago, my world was turned upside down when my daughter, Waverly, was diagnosed with Sanfilippo Syndrome. One month later, my son, Oliver, was given the same diagnosis. My family was living in London, embarking on a new career adventure when everything we had planned was no more.

My husband and I felt an extreme need to be back stateside to settle down, make a home, and build structure for the chaos we found ourselves now living. We were in a position where I could forgo my career to become the primary caregiver, devoting my time to the daily tasks of mothering two children with complex medical care needs. My husband worked to provide our family with insurance and financial stability. Most therapy appointments, doctor and equipment clinic visits, Medicaid applications, insurance appeals, and school forms were my responsibility.

In all the literature we read and conversations we had with other families, we were naïve about the impact severe neurological impairment would have on the children’s body systems as they neared the end of their lives. My husband and I made countless difficult decisions about their care. However, the most painful and gut-wrenching decisions revolved around feeding.

We opted for a G-tube when Waverly was 8 years old. She had been having trouble swallowing for several years. We thickened and puréed, but after some choking episodes, we had a g-tube placed. I took photos of her perfect belly and wept knowing our decisions were causing her to undergo surgery and pain. As parents, we weigh the options and make the best decision we can with the information we have at the moment. We constantly ask ourselves, “What is the ‘right’ decision?”

We continued with pleasure feeds, allowing Waverly to taste her favorite foods. We watched for signs of distress around eating, like squirming and crying. We noted signs of pain as we started a feed and then relief when we stopped. We would decrease rates and reduce volumes to maintain comfort. She began having more diarrhea and vomiting, spitting up formula during feeds. Waverly was experiencing edema throughout her body. We consulted with her team and made recommended changes, but her system continued to decline.

We had difficult conversations with providers we trusted. We weighed their guidance with our philosophy and ethics. I relied on my mother’s intuition, but Waverly was our guide. We followed her lead. Waverly was signaling to us that her body was tired.

It took time to see that feeding her was causing her pain. We charted every feed, how many milliliters and over what period. We noted any movement or grimace that we recognized as pain. We stopped and started, gave breaks, and switched to Pedialyte. We dripped tiny amounts of food into her belly only to stop as her body showed signs of distress. My husband and I both needed to agree that it was time to stop feeding.

It took time to see that feeding her was causing her pain. We charted every feed, how many milliliters and over what period. We noted any movement or grimace that we recognized as pain. We stopped and started, gave breaks, and switched to Pedialyte. We dripped tiny amounts of food into her belly only to stop as her body showed signs of distress. My husband and I both needed to agree that it was time to stop feeding.

We transitioned into a hospice approach focused on comfort. We had time to invite loved ones into our home to spend time with her, continue to make memories and build her legacy. She died in our bed days after she turned 12 years old.

I spent a significant amount of time perseverating on our decision to stop feeding her. I would be rendered inconsolable, and overwhelmed with guilt. My husband would walk me through the events, logically laying out the cause and effects, and why we came to our decision. Repeatedly organizing the facts allowed my emotional responses to quell. I needed that framework to assuage any guilt and confirm the decisions were made to alleviate the suffering of our daughter.

And we knew we had to do it all over again with Oliver.

We were practiced. Waverly once again smoothed the path for her little brother. We noticed the signs earlier and knew what adjustments to make. Our medical team was also more versed having navigated Waverly’s decline with us just three years prior. The decisions came quicker and with a tinge less doubt. Oliver died a few weeks before his twelfth birthday.

My guilt was lessened with Oliver’s death. I felt more confident in our decisions. I also felt more supported by all of those around me. My expertise was validated by Oliver’s care team.

As parents of children with rare diseases, we are often the experts in the room, explaining the nuances of our children to those more credentialed than we are. We bring binders and share literature to inform those caring for our children. We were fortunate to have a medical team who invited us to have a seat at the table for all decisions. And if they weren’t open to that, we found another provider who was willing to say, “I don’t know” and “let me consult with others”.

As parents of children with rare diseases, we are often the experts in the room, explaining the nuances of our children to those more credentialed than we are. We bring binders and share literature to inform those caring for our children. We were fortunate to have a medical team who invited us to have a seat at the table for all decisions. And if they weren’t open to that, we found another provider who was willing to say, “I don’t know” and “let me consult with others”.

Having abandoned a career and spent fifteen years as a full-time caregiver, I wanted to build upon my children’s legacy. I wanted to work in a field supporting children like mine. I returned to graduate school and became a pediatric social worker and grief counselor. I work for a community-based hospice and palliative care agency in Washington, DC.

As a pediatric hospice and palliative care social worker, I support families as they navigate complex decisions. I see my role as ensuring full parental participation and advocating for the parents’ goals of care. I am in their homes, supporting the entire family system, building trust and rapport, ideally early on so a relationship is established as decisions become more complex.

I have utilized the Courageous Parents Network both as a parent and as a professional. The educational videos were especially helpful in normalizing my experience as a mother. And I found it validating to hear others vocalize my thoughts and feelings. As a social worker, I return to the same videos with the families I support, hoping for a similar outcome.

The new NeuroJourney tool is invaluable. I wish I had access to this when I was parenting my children. However, I am thrilled to have this instrument available to my patients and their caregivers. I have introduced several families to the website, exploring the impact severe neurological impairment has on their child’s body systems. The website provides information and tools to parents and providers.

I have found the GI section especially helpful as it addresses a caregiver’s innate need to nourish their child. It provides a guidebook for one of the most challenging decision points. By using this tool, I have watched families recognize the signs of feeding intolerance and decline in their children. It opened the door to an honest conversation about prioritizing comfort and adjusting goals of care.

My hope, as both a bereaved parent who held onto guilt and as a therapist who supports caregivers experiencing guilt, is that this tool can aid in adjusting to changes and navigating decisions. This information has the potential to improve caregivers’ confidence in their choices by providing clinical data and reducing the potential for a more complicated grief process.

Theme: Feeding Tubes

The first time I fed my daughter was the day I met her in Guatemala City, when she was three months old. I held her tentatively as I offered her the bottle of the special formula my husband had gone to three farmacias to find. I marveled at her huge dark eyes and her perfect dollop of a nose. I softly sang the Hebrew lullabies that had imprinted on me when I was a baby, hoping they conveyed the love I already felt for her.

A few months later, we were given clearance by the Guatemalan and U.S. governments to adopt her. We named her Dalia and brought her home to our little family back in Boston. Now I was the mother of two, a baby daughter and a 3-year-old son. I juggled Dalia’s feedings with the thousands of things I did each day – working and potty training and begging the kids to nap; searching for lost toys and wiping tears and reading bedtime stories until I fell asleep.

Soon, Dalia was eating the Cheerios and cut-up grapes I placed on her high-chair tray. We brought home another baby the next year, and Dalia beamed while giving “her” baby his bottle, singing the lullabies I’d sung to her. Before long, Dalia was eating dinosaur-shaped chicken nuggets and smiley fries. She shared my weakness for potato chips. The two of us could go through a party-size bag in one sitting if my husband didn’t intervene.

When Dalia was diagnosed with MERRF Syndrome at age 5, we added a heaping bowl of applesauce to each meal to mask the array of medications she had to take. At 9, her disease erupted. A cold turned into pneumonia, landing us in the hospital for three months. She came home with a roomful of machinery – a fancy wheelchair, a ventilator, a food pump, and an array of equipment we didn’t want to believe our little girl needed. Dalia had a trach tube in her neck and a g-tube in her belly. The only thing she could eat was the Pediasure we poured into her pump bag each day.

Dalia hated not being able to eat even more than not being able to walk, so my husband and I tried to shield her from everything food related. We took turns eating dinner with the boys, while the other played with Dalia in her room. We hardly drove within a 100-foot radius of the supermarket if Dalia was in the car.

But then, the night before Dalia started at a new school that would cater to her complex needs, I read the schedule online. There, in between “Speech Therapy” and “Social Studies,” were two words that terrified me: “Cooking Class.”

“What are we going to do?” I asked my husband. “How can they make a child who can’t eat go to cooking class? Can we get her excused?”

“Let’s see how it goes tomorrow,” he said, “and then we’ll decide what to do.”

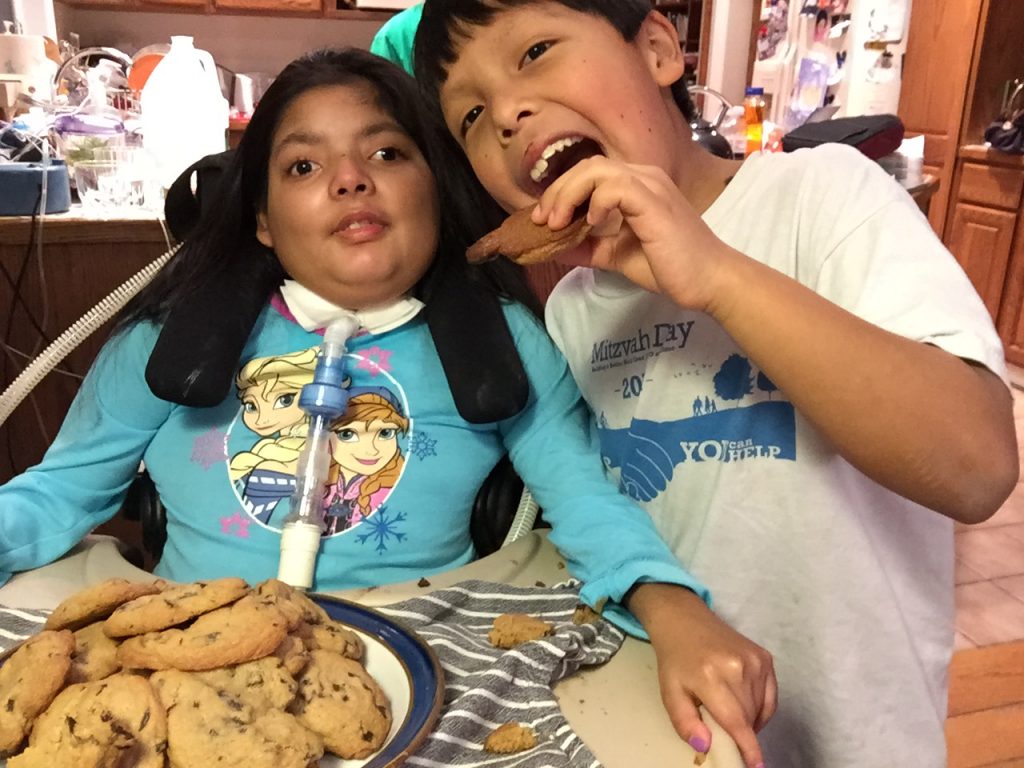

The next day, Dalia came home with a huge smile. The first thing she did was pull four chocolate-chip cookies out of her backpack. She handed one to my husband and me and one to each of her siblings. Then she watched with pride as we ate them and cooed over their deliciousness. When I emailed the teacher to check in, she said Dalia’s favorite part of the day was cooking class. She loved getting her hands gooey and watching the cookies take shape through the oven door.

The next day, Dalia came home with a huge smile. The first thing she did was pull four chocolate-chip cookies out of her backpack. She handed one to my husband and me and one to each of her siblings. Then she watched with pride as we ate them and cooed over their deliciousness. When I emailed the teacher to check in, she said Dalia’s favorite part of the day was cooking class. She loved getting her hands gooey and watching the cookies take shape through the oven door.

That night, Dalia asked if she could help make dinner. And then, since she’d helped make it, we sat together – all of us – at the kitchen table. Dalia commenced the festivities using a spatula as a baton. It felt like a reunion – the first time we’d spent dinnertime together since we’d returned from the hospital 18 months earlier.

After that, Dalia wanted to spend more and more time in the kitchen. She’d choose recipes from the troves of cookbooks that lined our shelves and help bake all kinds of delicacies that she couldn’t eat and I couldn’t resist.

Five pounds and a few weeks later, Dalia asked if we could all go out to dinner, a once-weekly routine we’d avoided since she got her g-tube. We were reluctant to agree – it was one thing to sit around the table together at home, where a typical family dinner lasts 15 minutes on a good night and where we could cut our losses if Dalia became upset. It would be another thing entirely to be in a restaurant where we’d be stuck waiting for the meal to arrive and where Dalia would be bored and potentially frustrated watching all of us eat.

But Dalia wouldn’t let it drop. Over and over again she pleaded, “Can we go out to dinner?” until she simply wore us down. We chose Legal Sea Foods, on the theory that Dalia could occupy herself watching the colorful fish in the tank if she became restless or frustrated. We brought coloring books and puzzles, so she’d have options of things to keep her busy while the rest of us ate. But we needn’t have bothered. Dalia was so happy to people-watch, and when the food came she wanted to stir my salad and help pour the dressing.

Dalia had always been the most social of our three kids, and somehow we’d taken away her opportunity to participate in the most social ritual we have. Gathering in the kitchen, preparing a meal, or going to a restaurant are about so much more than the food we consume. By trying to protect Dalia from feeling different or left out, we were doing exactly that – making her feel different and left out.

I’d watched every episode of “Clifford” with Dalia at least ten times. So how could I not have remembered the episode where KC, the three-legged dog, moves to town and the other dogs have no idea how to treat him? They overcompensate for his difference, not playing any of their usual games and instead choosing ones they think he’ll be able to play with them. They decide what KC can and can’t do without letting him weigh in for himself.

Now, we started to let Dalia be the guide – to let her take the lead on what she wanted to be part of. It went against every overprotective maternal bone in my body, but I had to stop trying to control situations for what I perceived to be Dalia’s benefit and instead let her tell me what was best.

Now, we started to let Dalia be the guide – to let her take the lead on what she wanted to be part of. It went against every overprotective maternal bone in my body, but I had to stop trying to control situations for what I perceived to be Dalia’s benefit and instead let her tell me what was best.

So we bought Dalia an apron and a chef’s hat, dubbed her “Little Chef,” and settled into the notion that dinner in our house was a full-family affair. We sat together around the dinner table every single night, right up until the one before she died last year. It was the one time of the day when we were all together just like any other family.

We listened carefully to what she needed to nourish her soul and let her happiness be our guidepost. And in the end, we found that what nourished her soul nourished the rest of us, too.

This blog is an adaptation of a piece that originally appeared on Medium.

Theme: Feeding Tubes

Feeding children is something we expect to do, with ease, as soon as our babies are born. It’s no wonder that when the child’s condition or treatment calls for a different plan, it’s straining.

This IN THE ROOM featured Dr. Dana Bakula, a pediatric psychologist specializing in assisting families of children with medical complexity. She is the Co-Director of the Interdisciplinary Feeding and Swallowing Program at Children’s Mercy Kansas City and the Assistant Professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine. Dr. Bakula serves as both a clinician and a researcher, dedicated to crafting interventions that aid caregivers facing feeding challenges. Joining Dr. Bakula in this conversation was Nicole Crump. Nicole is the mother of two children, including one who has an ultra-rare medical condition and complex needs. She is a dedicated advocate for caregiver needs.

Theme: Feeding Tubes

Theme: Feeding Tubes

Theme: Feeding Tubes

Theme: Feeding Tubes

In this Zoom interview with CPN, Michelle — mother of Alex (age 7) and Julianna, who had a severe form of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and died at age 5 — shares how the feeding tube intervention was to help Julianna get nutrition but led to medical complications. Julianna went from the G-Tube to the GJ-Tube.

Theme: Feeding Tubes

From Coalition for Compassionate Care of California.

A feeding tube is used when a child can’t take in enough food or safely swallow because of an illness or chronic health condition. Nutrients go into the stomach through a small flexible feeding tube.

It can be a difficult decision for parents and the healthcare team to decide when or if tube feeding is right for a child.

This guide includes helpful information about different feeding tubes, including some questions about tube feeding that parents often ask.

Theme: Feeding Tubes

I was determined to do everything possible to save her from a Gtube. … but it got to the point where had to do something different.” A mother of an infant with serious apnea and aspiration talks about how reluctant she and her husband initially were to giving their daughter a feeding tube. She describes the process that led to their decision to get the G-tube and how they have adapted. “We got to the point where we had to do something different.”

Theme: Feeding Tubes

Charlie and Tim Lord, twins, and fathers of Cameron and Hayden respectively, talk about how their conversations with parents that had gone before helped them consider all the options and find what was best for each of their families. There isn’t only ONE way. There are no SHOULDs.

Theme: Feeding Tubes

In this clip from Courageous Parents Network’s virtual video interview with Brenda Murray, Brenda thoughtfully shares the spectrum of interventions they considered and the decisions they ultimately made for Sam as they balanced the risks vs benefits: Yes to Feeding Tube, No to Hip Surgery, No to Spinal Fusion, No to Trach. These are all big decisions. “There is a lot of guilt. What if you don’t do it?”

The doctor looked at me and said, “You’re not a bad mother if you decide not to do this.”

She talks about who her sounding boards were — family, social worker, pediatricians.