-

A diagnosis of Krabbe; and the medical t...

-

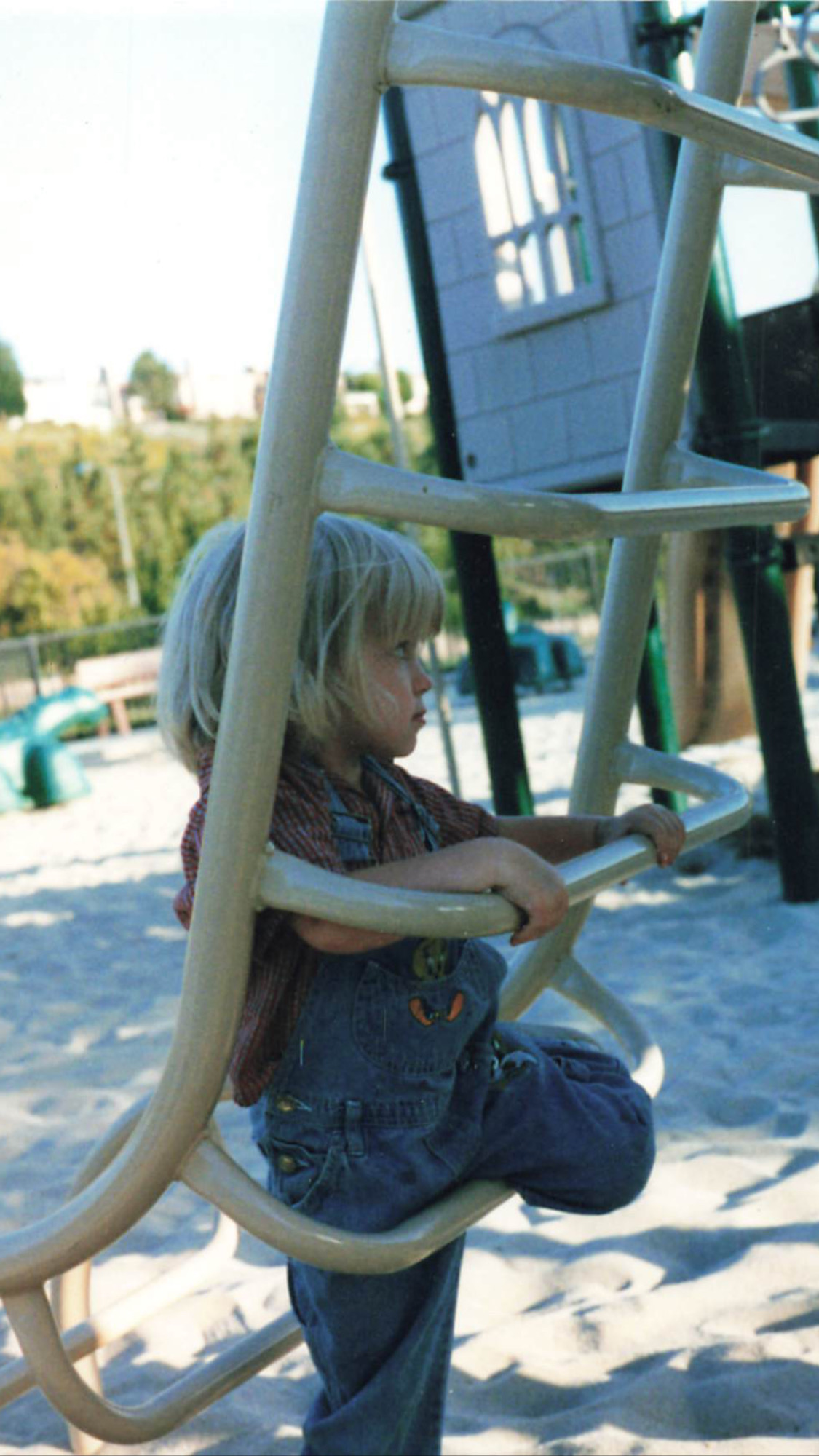

We were so caught up in having a new bab...

-

Adding Hospice to the Care Team

-

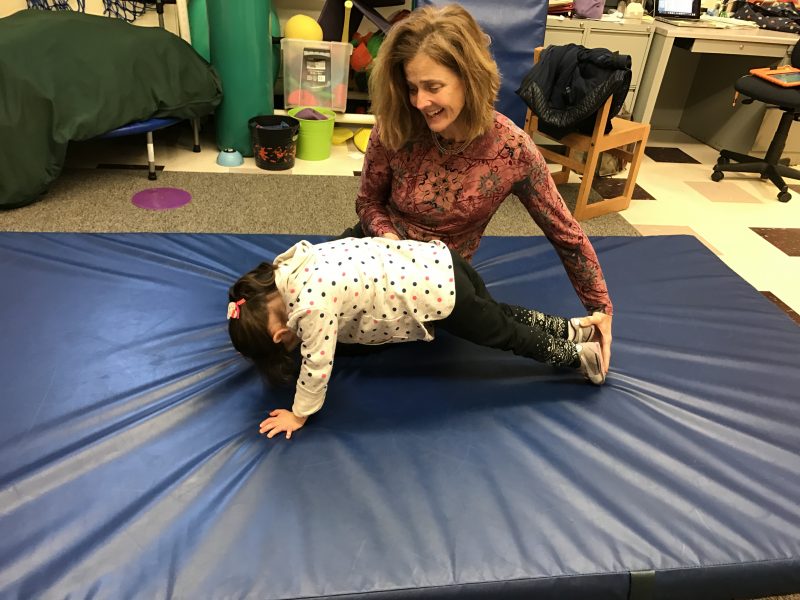

What does a “good day” look like? Em...

-

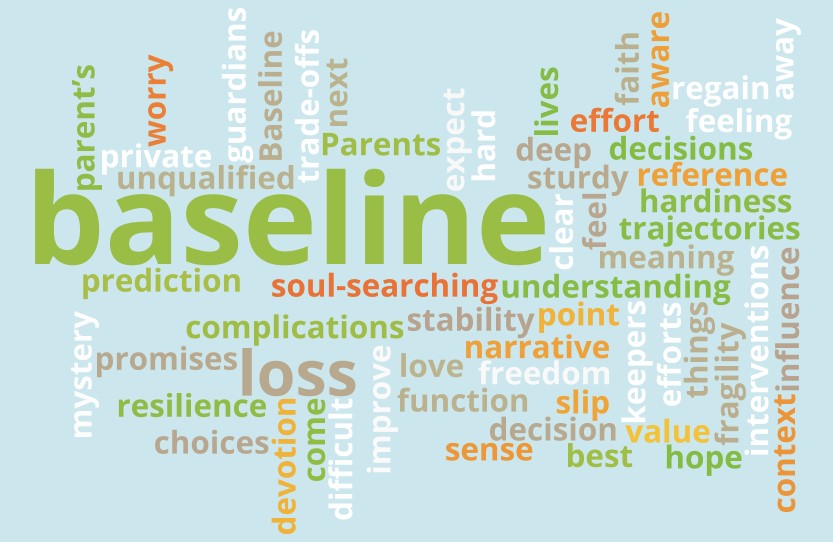

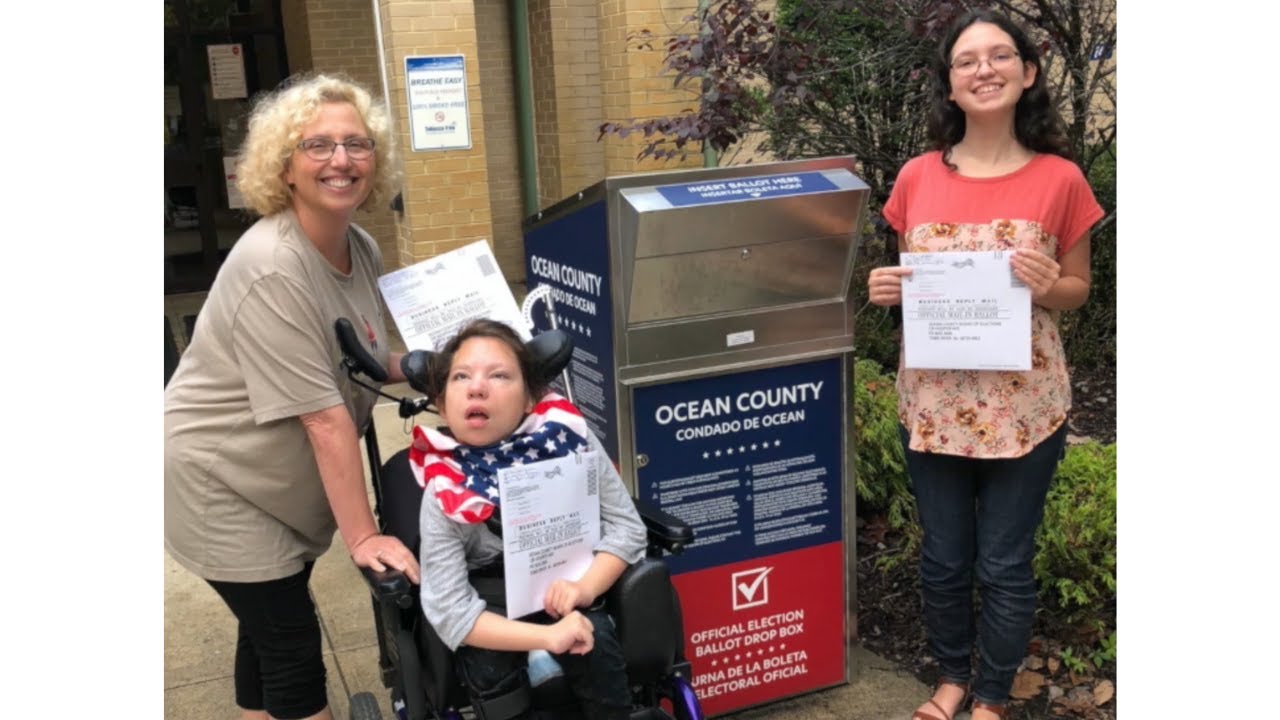

This is How We Live: This Thing Called B...

-

Problems of the CNS: Is this a new acute...

-

Intractable problems and a new Baseline:...

-

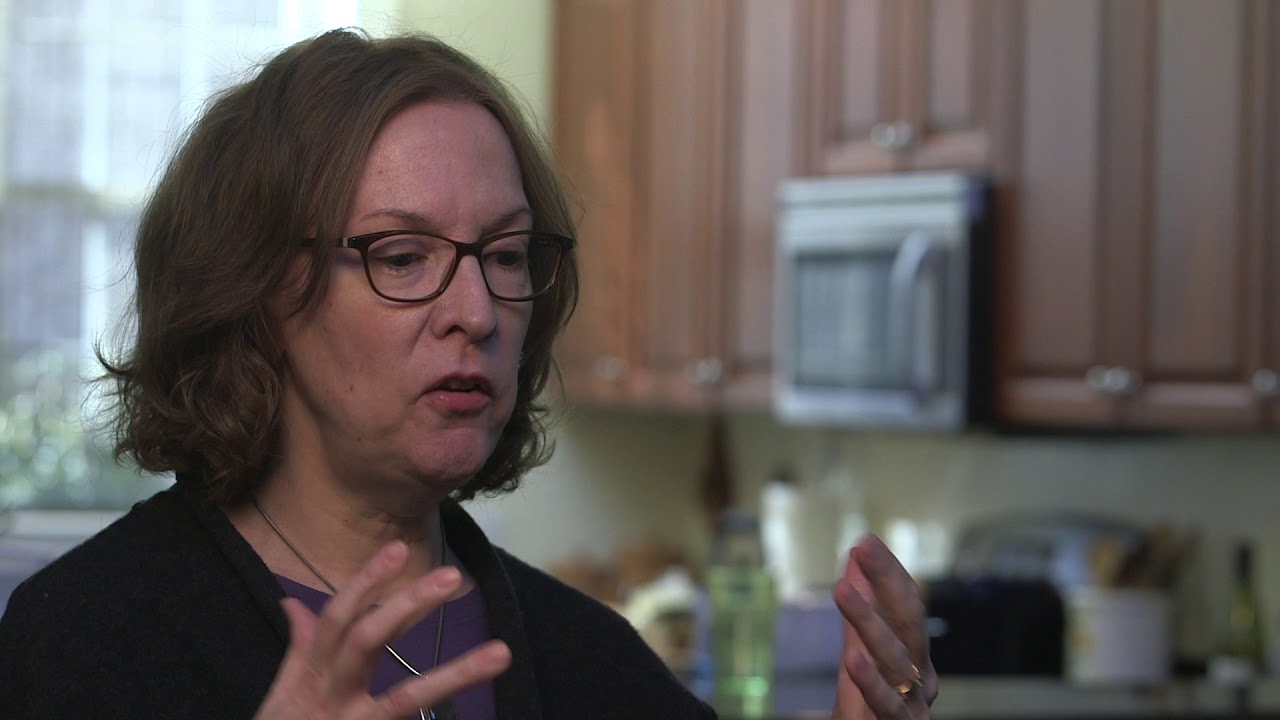

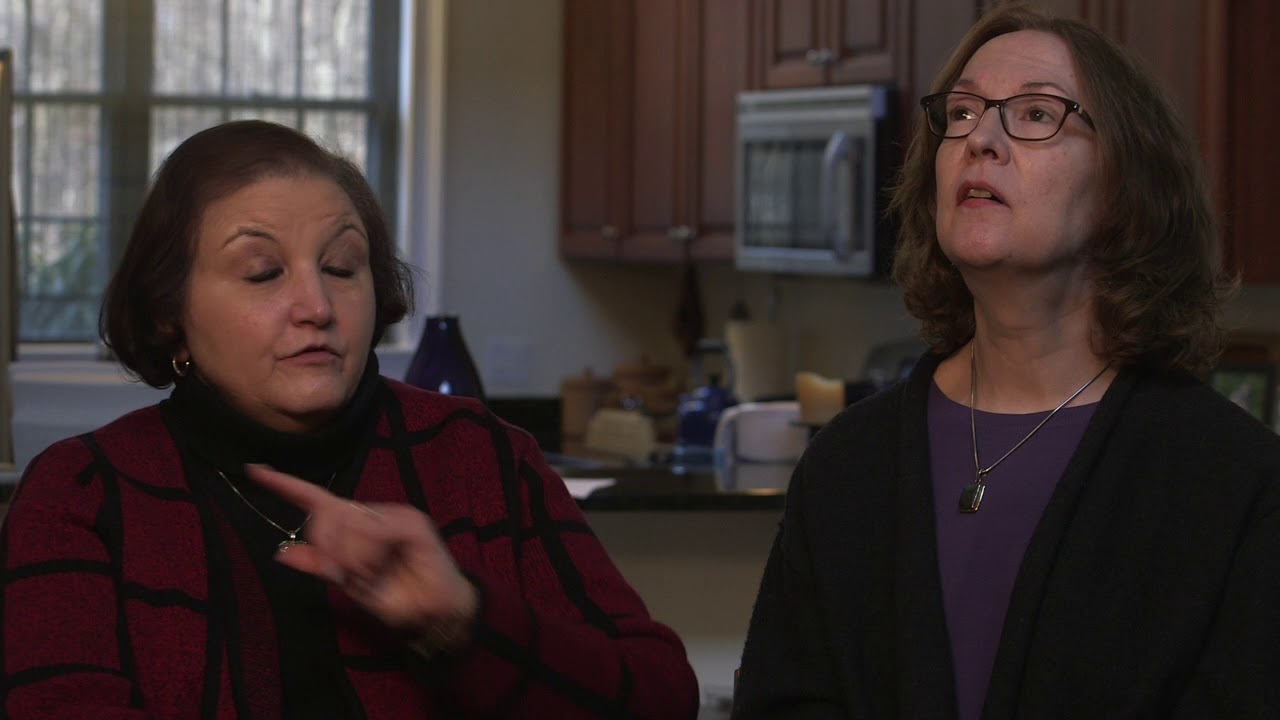

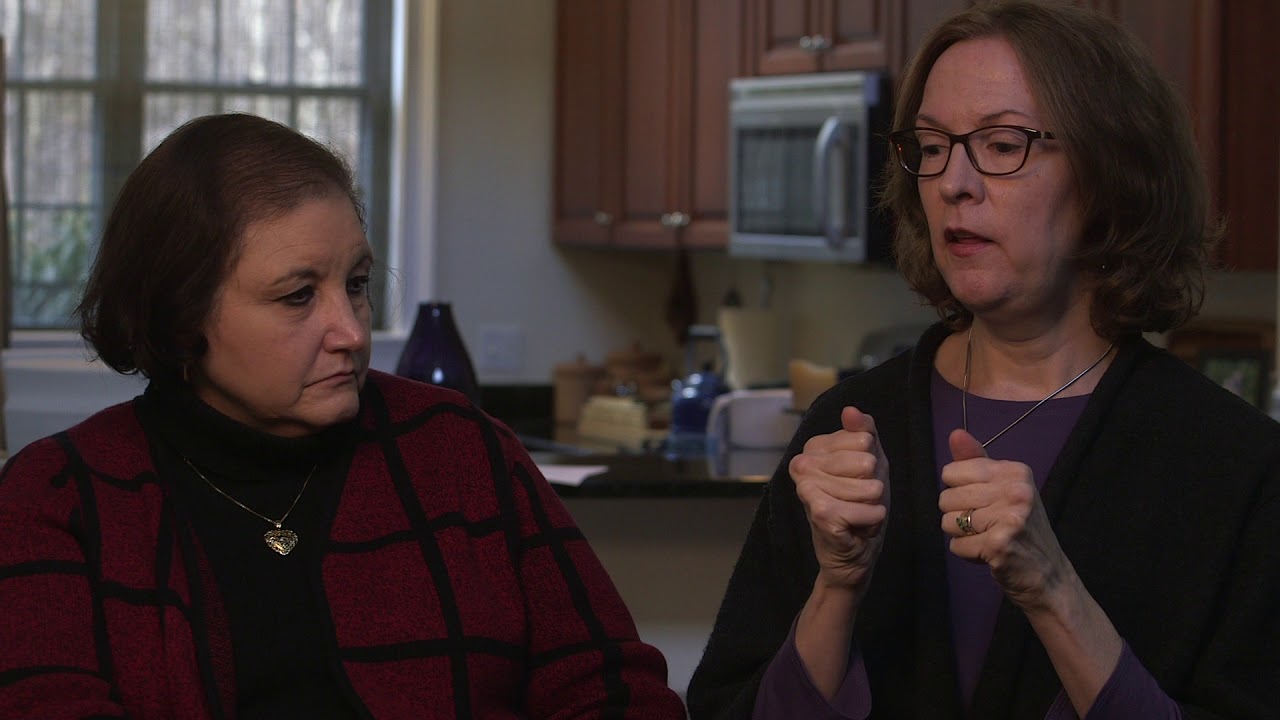

The Conversation and Advance Care Planni...

-

Palliative care helps parents pause and ...

-

Always give them a sense of what’s goi...

Videos

Theme: Baseline

A diagnosis of Krabbe; and the medical team getting to meet him before his condition progressed.

A diagnosis of Krabbe; and the medical team getting to meet him before his condition progressed.

SHARE