Receiving the Diagnosis

Learning of your child’s disease or illness is a life-changing moment. If the journey to diagnosis has been long or uncertain, you may feel some relief: now at least you know. You might feel anger or resentment if you believe that with an earlier diagnosis things might have been better—especially if you feel that your earlier concerns and instincts were dismissed. If the diagnosis was completely unexpected, you may feel shocked and confused. Parents agree that whatever you are feeling at diagnosis, hearing the news is one thing and adjusting to it is another.

Your Team:

A member of the clergy who is responsible for the religious needs of an organization and/or its constituents.

A specialist whose aim is to improve the quality of life of their patients over the course of their illness regardless of stage, by relieving pain and other symptoms of that illness.

A medical professional who practices general medicine.

A mental health professional who uses therapy and other strategies to support coping and adjustment and treat concerns regarding social, emotional, or behavioral functioning.

A trained professional who works with people, groups and communities to help them better their lives.

An individual who leads and/or guides individuals or groups coping with life experience and challenges.

A pediatric health care professional who works with children and families to help them cope with illness, injury and other medical experiences.

A specialist in evaluation, diagnosis, and management of patients with hereditary conditions.

Groups that represent and support patients and their families/care partners.

A specialist in evaluation, diagnosis, and management of patients with hereditary conditions.

A child-life specialist can provide support to your entire family. Palliative care clinicians, a psychologist, social worker, chaplain and/or spiritual leader can provide a space for talking through your initial feelings and then your ongoing concerns. Your child’s primary physician can also be a good resource, especially if they already know your child and family well and can see the big picture of your family’s experience. A genetic counselor can help you understand the genetics of the diagnosis, explore potential implications for other family members, and support you in processing emotions. Patient organizations focused on your child’s diagnosis can be a place to find support.

And soon enough there will be information to gather, clinicians to meet, teams to assemble, new systems to learn, arrangements to be made at home and work. Although you may wish for a prognosis or other specific information, the clinicians may not be willing or able to speculate. The truth is that many conditions have a range of prognoses and expectancies. If you want detailed information, ask the care team to be as specific as they can be, based on their experience with similar conditions. Depending on how they speak to you, you may feel frustrated or you may feel supported. If they use vague language or unfamiliar terms, ask them to explain in specific terms you can understand. You have a right to give feedback about this and to ask for their help in understanding.

Then there will be decisions to make. In some cases, you will have time. In other cases, the care team may want immediate direction from you. In an ideal world the team members would be mind readers and know exactly what you want without your having to say. In reality, though, clarity about your concerns and your goals will generally emerge through multiple conversations. You can slow things down. You can ask for at least moments to orient yourself and others around you to this new reality. You can ask for guidance from the physicians, spiritual leaders, or anyone else who you feel you can trust.

If you feel that the medical team is deferring too much to you but not giving you information to inform your decisions, you can ask for help in identifying all the issues to consider and talking them through. Palliative care professionals are specially trained to be with families through these difficult circumstances.

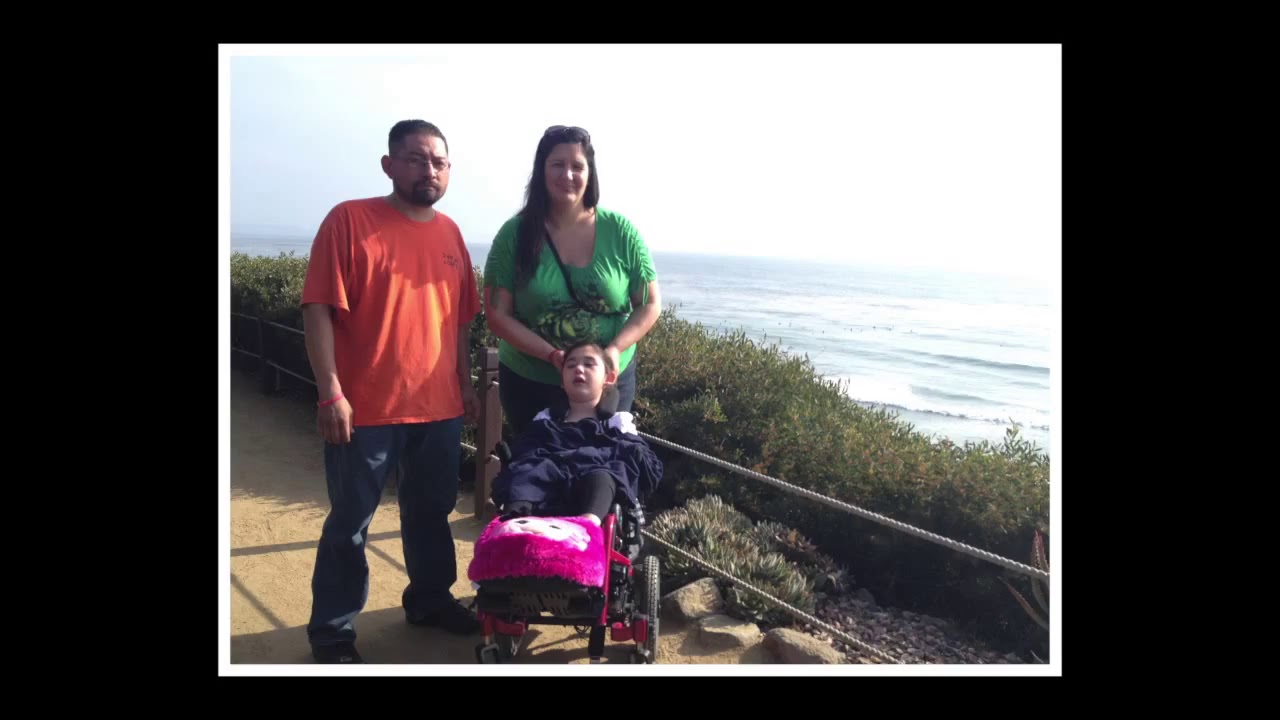

– Kerri, parent of Kai

Diagnosis and Anticipatory Grief

You may experience anger toward the clinicians. You may blame yourself or your parenting partner for what you did not know, or feel guilt for having carried a genetic disorder. You may worry for your other children, if you have them. If you have a spiritual practice, it may be strengthened. Or, you may now have doubt and feel unsure.

Fear, guilt, questioning and anger are natural responses to very bad news, but most of us don’t immediately identify what we are feeling as loss, and don’t identify our feelings as grief. But there is a kind of grief for the many experiences and losses to come. Most families find it helpful to know that there is a name for this: anticipatory grief. Knowing that you and others in your family are feeling anticipatory grief, and are likely to experience it again at other times, will allow you to be compassionate and gentle with yourself and others.

To learn more about anticipatory grief see the CPN guide “What is Anticipatory Grief?” and visit the section Anticipatory Grief.

Palliative Care—Not Hospice

PPC clinicians can support you in processing your feelings and concerns, defining and advocating for your priorities in your child’s care, and finding ways to care for your other children if you have them. The medical team may suggest a palliative care consult. If they don’t, you should feel free to request one. Most families say that palliative care makes all the difference in how a family copes, feels and navigates the journey.

To learn more about palliative care see the CPN guide “Introduction to Palliative Care.”

Related Resources

-

There’s a fine line between hope and acceptance.video

There’s a fine line between hope and acceptance.video -

After Diagnosis – Gaining More ‘Family'BLOG

After Diagnosis – Gaining More ‘Family'BLOG -

A diagnosis of Krabbe; and the medical team getting to meet him before his condition progressed.video

A diagnosis of Krabbe; and the medical team getting to meet him before his condition progressed.video -

The Doctor Shuffle, Diagnosis Rett SyndromeBLOG

The Doctor Shuffle, Diagnosis Rett SyndromeBLOG -

The diagnosis didn’t change anything. We were still just treating symptoms.video

The diagnosis didn’t change anything. We were still just treating symptoms.video -

“We were not ready for her actual diagnosis.”video

“We were not ready for her actual diagnosis.”video