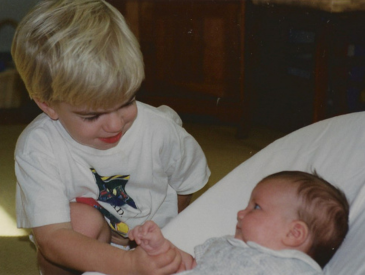

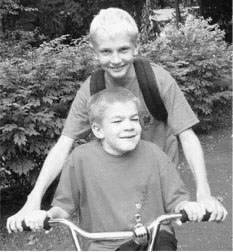

Siblings

Each member of your family will experience this loss, each in their own way. Your other child(ren)’s response may not be quite like your own. Parents very often feel pressure to manage the normal responsibilities of parenting their other children while tending to their own grief. It’s a lot to manage. Although children can be very resilient, how well parents cope with the loss of their child has a direct impact on how well the siblings will fare over time. And you may find that the more you see the siblings doing well, the more comforted and confident you will feel.

Your Team:

A member of the clergy who is responsible for the religious needs of an organization and/or its constituents.

A mental health professional who specializes in bereavement and loss.

A specialist whose aim is to improve the quality of life of their patients over the course of their illness regardless of stage, by relieving pain and other symptoms of that illness.

A mental health professional who uses therapy and other strategies to support coping and adjustment and treat concerns regarding social, emotional, or behavioral functioning.

A trained professional who works with people, groups and communities to help them better their lives.

A person who gives help and advice to students about educational and personal decisions.

A person trained to care for the sick, especially in a hospital.

A medical professional who practices general medicine.

An individual who leads and/or guides individuals or groups coping with life experience and challenges.

An educator.

A psychologist, social worker, chaplain and/or spiritual leader can provide a safe space for siblings to talk and share their feelings. A grief counselor can help process strong emotions. Palliative care clinicians and child-life specialists can offer age-appropriate ways of talking with siblings and facilitate special moments and memory-making. Your child’s primary physician can offer a deeper understanding of the family. A school nurse, guidance counselor, or teacher can provide support. Connection to other families that have lost a child can be helpful.

Every individual experiences loss, and this includes even the youngest children. Their sense of what life is “supposed” to be like has changed. Developmental stage, cognitive level, life experiences, losses in the past, and other exposure to death may influence a child’s understanding. Parenting may feel like an extraordinary burden, especially when you yourself are grieving. As a practical matter, you can use your understanding of how children perceive and react to death for approaching this subject and supporting siblings in ways that are developmentally appropriate and helpful. The Courageous Parents Network guide “Parenting the Surviving Siblings” is a comprehensive resource for navigating the sensitive issues that may arise.

Understanding that each child develops differently, here are some general guidelines for how children grieve at different stages:

- Infants have no cognitive understanding of death, but they do grieve. They may experience death as separation, and often sense a caregiver’s emotional state. There may be changes in their eating, sleeping or other behaviors. It is important to maintain routines and avoid separation when possible.

- Preschool children (ages 2-5) see death as temporary and reversible. Magical thinking (around age 5) starts around this age, and so children may believe that a death is the result of something they did or didn’t do, or that they somehow caused the death.

- Children ages 6-9, like younger children are concrete thinkers. They still do not understand that death is permanent. They may worry that it will happen to them or to someone else they know.

- Children ages 9-11 remain concrete thinkers. They have some capacity to put themselves in other people’s shoes and may have a sense that others can die.

- Around age 12, children begin to have abstract thinking and come to understand that death is final, irreversible, and will happen to everyone.

- Adolescence has many phases and each phase may bring with it different responses.

– Connor, sibling of Lauren

How Grief Shows Up in Children

Enlisting Helpers

Keeping the Dialogue Open

As has always been true along this journey, it is vitally important that you care for yourself. Remaining strong and resilient, emotionally and physically, is a gift both to you and for the others who not only need you but love you and care for you.

Related Resources

-

As parents, we can dose ourselves with the pain, and then regroup for our children.video

As parents, we can dose ourselves with the pain, and then regroup for our children.video -

Bereavement: Dr. Breyer on supporting the siblingsvideo

Bereavement: Dr. Breyer on supporting the siblingsvideo -

A bereaved sister keeps her brother’s legacy: learning gratitude, telling his story, helping other kidsvideo

A bereaved sister keeps her brother’s legacy: learning gratitude, telling his story, helping other kidsvideo -

No Sign of a SignBLOG

No Sign of a SignBLOG -

Writing as Healing: A Conversation with Two Siblings.video

Writing as Healing: A Conversation with Two Siblings.video -

Parenting the Surviving Siblingsguide

Parenting the Surviving Siblingsguide -

A Mother and Son Explore Griefaudio

A Mother and Son Explore Griefaudio