9/14/2022

·Enable high contrast reading

I used to wonder if I would know when I was in love. People say it’s a feeling like no other, and you’ll know when you know. But would I? Having never experienced it, would I recognize the feeling? Would I truly know if I was in love with someone and they were in love with me? When it happened, I recognized it. I knew. Instinctively, I knew. During my first pregnancy, I worried if I would know when I was going into labor. Or would I be the first time mom that heads to the hospital again and again with what I thought were real contractions just to be sent home and be told to wait for the real thing? I needn’t have worried. When the time came, I knew.

When our daughter’s cancer relapsed, her chances of surviving the disease were diminishing. Her scan results used to be more definitive, we used to hear encouraging news like the tumor shrank by half, or the smallest lesions on her lungs can’t be seen on this recent scan. Now we heard things like; This scan wasn’t as clear as we would have liked to see. Things didn’t get worse, but they didn’t get better. Did a new tech run this? Lauren’s recent pneumonia made the pictures of her lungs blurrier than last time, so it’s hard to see if the tumors shrank. This happened over the course of a couple of months. We began to wonder why the chemo wasn’t working like it used to. It was unsettling. And scary.

During her recurrence, I remember meeting our palliative doctor on the way back from the cafeteria where I ran to get Lauren some lunch. We were alone in the hallway. I don’t like where this is going, I said. I’m really scared. Our palliative doctor, whose advice I’d come to seek before anyone else’s, said, I don’t like it either. How will I know? I asked her. How does this work, I mean, are we going to come to the clinic some morning and you’ll tell us she’s dying? Is that what happens? I think she said, It may be more gradual than that. Lauren may not feel as well. She may start to have more bad days than good ones. Her counts may take longer to rebound. She might require more frequent transfusions. Scans may stop having neutral news and have bad news. It’s not happening now. But if you’re wondering if you’ll know, I think you will. But would I?

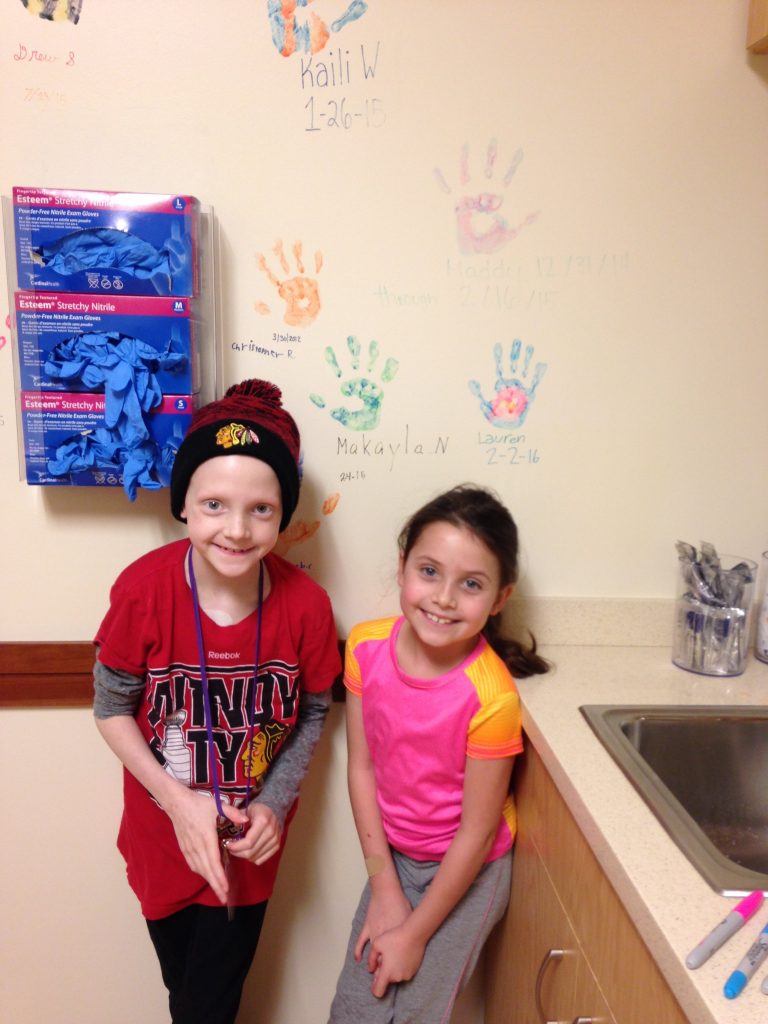

Throughout her diagnosis, Lauren would have big worry days. These days would crop up every few weeks, more so at the beginning of her diagnosis. Her big worry was that she was dying. In the car or the waiting room, she’d whisper close, I have my big worry today. And then she would rely on me to tell her doctors. Lauren has a big worry today, I’d tell her oncology team. She’s worried she’s dying. They always treated her big worry so sacredly. I remember they would stop, and we’d all stay quiet for a moment. And they would tell her, Lauren, we will always be honest with you. Please know we will always be honest. And we will tell you if you are dying. And we can honestly tell you that you are not dying today. I remember wanting them to stop at “you are not dying” and forget about the “today”. Why add that? It’s such a scary and depressing thought. She’s only a kid and you’re going to scare her I thought. You’re sure scaring me. Later I realized, they were keeping their word. They were being honest.

Throughout her diagnosis, Lauren would have big worry days. These days would crop up every few weeks, more so at the beginning of her diagnosis. Her big worry was that she was dying. In the car or the waiting room, she’d whisper close, I have my big worry today. And then she would rely on me to tell her doctors. Lauren has a big worry today, I’d tell her oncology team. She’s worried she’s dying. They always treated her big worry so sacredly. I remember they would stop, and we’d all stay quiet for a moment. And they would tell her, Lauren, we will always be honest with you. Please know we will always be honest. And we will tell you if you are dying. And we can honestly tell you that you are not dying today. I remember wanting them to stop at “you are not dying” and forget about the “today”. Why add that? It’s such a scary and depressing thought. She’s only a kid and you’re going to scare her I thought. You’re sure scaring me. Later I realized, they were keeping their word. They were being honest.

I am immensely proud of Lauren that she was able to articulate that big worry. My introverted, soft-spoken, shy 7-year-old gave voice to the biggest worry. My child, who when she tried a new food at the dinner table made everyone close their eyes because she was too bashful to see everyone’s reaction, was able to give voice to most adults’ biggest worry. Our Lauren said it out loud. Scary and hard words out loud. What a privilege, what an honor that Lauren trusted me to be her voice. Our oncology and palliative teams responded with such kindness and honesty. Each time it came up, they met my child’s big worry with the sanctity it deserved. To say they created a safe space for Lauren doesn’t go far enough. They created a protective barrier between Lauren and cancer. They wove this emotional safety net where you can say the hardest thing here, and it will be held and honored, and we will help you feel protected.

As cancer treatment got more routine, Lauren still had big worry days. But she now knew if her counts were down, it didn’t mean she was dying; it likely meant a transfusion was needed, and maybe an overnight hospital stay. During some chemo cycles, while waiting for the lab to send back her counts, she’d say, I need a transfusion. I can feel it. She knew her body and she was right. She’d miss school and we’d have to use the overnight bag I always carried with us. She hated that bag.

Two years after Lauren was diagnosed we took a trip to the beach. It was a bit of a make-up trip, as we had planned a trip like this the exact week Lauren got diagnosed, and had to cancel it. This time we traveled with a cache of medication, injections, and thermometers. Lauren’s oncologist helped me plot out the drive and identify which hospitals along the route we should stop at if Lauren fell ill. I remember looking at the map during the drive, and thinking okay, for the next 2 hours, the closest hospital is ours. For the next 3 hours, if something happens, we’ll go to St. Jude’s or double back. The drive there and back was one prolonged anxiety attack watching dots on my map approach and pass.

On a walk along the beach with my husband Dan, we held hands and looked at the sunset. I don’t think Lauren’s going to survive this, I told him. I don’t either, he said. Neither of us had ever said this out loud to each other. How long have you thought that? I asked. I don’t know, he said, a little while I guess, it’s been coming to me gradually. Me too, I said. But I’m nearly sure now. Yeah, me too. What do you think we should do? he asked me. I don’t think she knows yet, I think she will tell us if she’s feeling it. I don’t think the other kids realize either, I said. As much as we can, I think we should let her be a kid. Let them all be kids. And let’s hope and trust we recognize the right time to tell them.

For the next few months, we didn’t tell anyone about our conversation. I searched for patterns of decline: was she having more bad days than good? How many hours did it take for her counts to rebound this cycle? Was it longer than last time? We tried to give Lauren as many normal and special experiences as we could. She desperately wanted to be a normal 4th grader, so she attended school every day possible. She played with her siblings and her friends. She did some chores, fed the dog, and made her bed. In between treatments and school, we made time for special moments. Lauren had overnight visits with her cousins. She went to the lake house. She visited her grandparents. She went on a field trip. We went to the movies.

Driving to school one morning, Lauren and her twin sister Emma were on the lookout for cute dogs. Both girls told me the kind of dog they planned to get when they grew up. This was a recurring and evolving conversation for years between the three of us. We had already mulled over this topic 100 times. Now talking about it was both the sweetest and most excruciating thing. I could barely withstand it. I don’t recall what kind of dog either wanted. I was too struck with the thought that Lauren wouldn’t grow up.

Weeks later on Halloween, the girls were planning their costumes. I know what I want to be this Halloween, and maybe next year Lauren commented. Mom, what do you think I should be next Halloween? I don’t know honey, I said, pretending to look for something on the floor. I think you can be anything you want. Next Halloween felt like light years away. It crushed me to think about it. Please let her make it to this Halloween I thought. Please stay strong enough to be a kid this Halloween.

Weeks later on Halloween, the girls were planning their costumes. I know what I want to be this Halloween, and maybe next year Lauren commented. Mom, what do you think I should be next Halloween? I don’t know honey, I said, pretending to look for something on the floor. I think you can be anything you want. Next Halloween felt like light years away. It crushed me to think about it. Please let her make it to this Halloween I thought. Please stay strong enough to be a kid this Halloween.

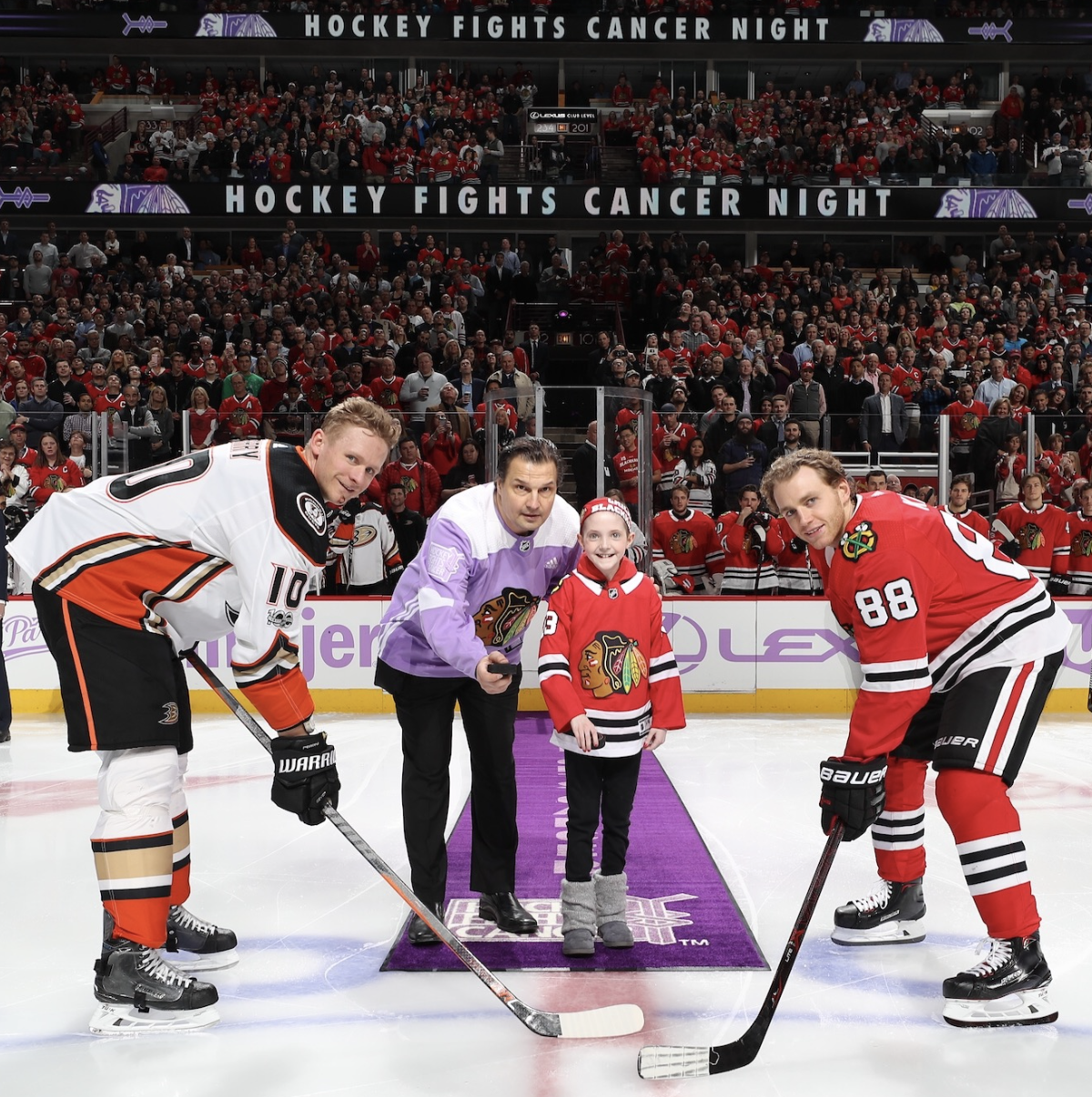

That November, Lauren was selected as the pediatric cancer ambassador to drop the puck for her beloved Chicago Blackhawks at their NHL Hockey Fights Cancer Night. It was the best day of her life. She was out on center ice with a crowd of 21,000 fans cheering for her. She waved like a pro and her smile lit up the United Center. What a gift for Lauren to get this day. Dan and I watched from the stands. We squeezed each other’s hands. Please let us know when to tell her. I hope we know.

Amy Graver currently works in the corporate world, and is a writer, a wife, and mom of four. Her daughter Lauren was diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma at age 7. Amy’s writing chronicles the journey on which cancer has taken her family. Lauren’s cancer diagnosis imposed a new reality and a new perspective on life. She is dedicated to making the cancer experience better for future families. Amy is an enthusiast of US presidential history, she aspires to be a professional seashell collector, and is absurdly competitive about things that don’t matter.

You'll Know