Category: Sanfilippo syndrome (MPS)

There is a post going around on Facebook about dementia. On one hand I can appreciate it but on the other I can’t. To me, it lacks recognition of a big audience impacted by dementia – children.

It goes like this …

Someone once said, “When you love someone with dementia you lose them more and more every day. When they are diagnosed, when they go through different stages, when they go into care and when they die. ‘Rapidly shrinking brain’ is how doctors describe it. As the person’s brain slowly dies, they change physically and eventually forget who their loved ones are. They can eventually become bedridden, unable to move and unable to eat or drink. There will be people who will scroll by this message because dementia has not touched them. They may not know what it’s like to have a loved one who has fought or is fighting a battle against Dementia. To raise awareness of this cruel disease, I would appreciate it if my friends could put this on their page for today. A special thank you to all willing to post to their timeline.

I empathize with the people who share this post, and the many who comment about their mom, dad, uncle, aunt who have suffered the ravages of dementia. Dementia is ugly cruel! It slowly peels back and robs you of the layers that make a person whole. It leaves you lonely, misunderstood and incredibly lost when you feel forgotten by the person who suffers from it.

I have experienced it first hand but not in the way most do, with an elder. I watched my son Ben, diagnosed with the rare disease Sanfilippo Syndrome, regress into childhood dementia. I describe it as slowly watching Ben fade away – a person once opaque slowly becoming transparent. Nine years after his death, I can still taste the fear of invisibility – him to me and me to him – in the back of my throat.

I have experienced it first hand but not in the way most do, with an elder. I watched my son Ben, diagnosed with the rare disease Sanfilippo Syndrome, regress into childhood dementia. I describe it as slowly watching Ben fade away – a person once opaque slowly becoming transparent. Nine years after his death, I can still taste the fear of invisibility – him to me and me to him – in the back of my throat.

I want to post a comment to show I KNOW and tell them about my experience with dementia – how it started to rear its ugly head when my son was not yet 5 and how by the time he passed away at 17 it had stolen away his ability to talk, walk, and even support his own body weight. I want to tell them how it left only rare moments of eye contact or the slight turning up of his lip, to tell me that some happiness, some piece of him still resided within. I want to hit the Share button as a way to say SEE me and all the other families whose children will suffer dementia as a devastating dimension of their underlying disease.

But I don’t.

I cannot help but see the greater unfairness. The fathers, uncles, sisters, mothers lived full lives. The layers of their lives had a chance to build to whole before dementia slowly started to peel away their essence. In so many pediatric rare diseases, the onset of the “rapidly shrinking brain” occurs so early that the child has not even begun to become the person that a normal life would allow them to grow into. These children disappear before we truly get to know their personality, their passions – the them that makes them who they were meant to be.

As a parent, this is heart-wrenching torture, but as the sibling, it is utterly tragic. Adult siblings who watch their brother or sister move closer to forgetting them, have a lifetime of memories and a deep-rooted knowledge of who their sibling was before dementia robbed them of their essence. The siblings of a child with pediatric dementia are cheated out of the opportunity to deeply know their sibling – not only because they will not know a lifetime of shared experiences but also because their sibling is disappearing as they themselves are growing. Families are left to fill in the gaps – assigning characteristics and traits to the dementia-plagued child, based on some insight into what the child might have grown up to love, do, or think. This gap-filling is especially hard on the siblings. With so few memories to draw from, many formed when they are young themselves, the siblings live with the pressure and constant fear of forgetting their brother or sister, even before they die.

As a parent, this is heart-wrenching torture, but as the sibling, it is utterly tragic. Adult siblings who watch their brother or sister move closer to forgetting them, have a lifetime of memories and a deep-rooted knowledge of who their sibling was before dementia robbed them of their essence. The siblings of a child with pediatric dementia are cheated out of the opportunity to deeply know their sibling – not only because they will not know a lifetime of shared experiences but also because their sibling is disappearing as they themselves are growing. Families are left to fill in the gaps – assigning characteristics and traits to the dementia-plagued child, based on some insight into what the child might have grown up to love, do, or think. This gap-filling is especially hard on the siblings. With so few memories to draw from, many formed when they are young themselves, the siblings live with the pressure and constant fear of forgetting their brother or sister, even before they die.

And then there is the way children with pediatric dementia are viewed out in their community. These children are not given the forgiveness that is afforded to the increasingly forgetful father. Instead, they are mistakenly labeled as behavior problems. I will never forget the woman in the supermarket who chastised me for allowing Ben to repetitively push the grocery cart into me. I wanted to yell at her, “He’s forgotten how to stop. He only knows that when his hands are on the handle he needs to push,” but her mind was already made up.

Children who experience pediatric dementia are often also misunderstood in the medical world. Many suffer years without a diagnosis and incorrect or inadequate medical care. Even with a diagnosis, research into dementia is largely adult-based, so pediatric providers lack strategies to help families who are caring for these children. When Ben was 9 and experiencing a two-year long period of little-to-no sleep, and panic attacks so extreme that I thought he was hallucinating (all symptoms of dementia), the solution the medical world offered me was placement in a psychiatric unit (without a parent) and a regiment of lithium. In those long days I found myself researching Lewy-Body dementia, finding a specialist in circadian rhythms, purchasing sun lamps to tackle sundowning, and suffering the deepest despair I have ever felt over my inability to help my child.

Dementia is lonely for ALL whose loved ones pass into it. And the world certainly needs to stop looking away as families face this unimaginably cruel way for someone to pass from this earth. Recently, a very wise pediatric palliative care doctor shared these words with me,“While most of the rest of the world flees a sorrow that deep, having someone here or there who at least will not run away and can stand still, –even if they can’t bear to lean in fully—says something.”

Dementia is lonely for ALL whose loved ones pass into it. And the world certainly needs to stop looking away as families face this unimaginably cruel way for someone to pass from this earth. Recently, a very wise pediatric palliative care doctor shared these words with me,“While most of the rest of the world flees a sorrow that deep, having someone here or there who at least will not run away and can stand still, –even if they can’t bear to lean in fully—says something.”

So yes, I want to post a comment. I want to ask others to lean in or at least not run away. I want them to SEE childhood dementia. But I can’t post. I’m too afraid that if I do and they don’t respond, another layer of my son Ben – the layers that now reside only in my memory and in my heart – will peel away.

Category: Sanfilippo syndrome (MPS)

I attended a conference last week. The keynote presenter, a scientist turned venture capitalist, titled his talk “Rational Hope”. He spoke to an audience largely comprised of industry leaders and scientists about research breakthroughs, citing PKU and Gaucher as historical examples of a treatment coming to market successfully and in a relative quick manner. I believe his end goal was to illustrate how exponential advances in science have shortened the lab to patient timeline allowing today’s patients to have rational hope for a treatment.

I attended a conference last week. The keynote presenter, a scientist turned venture capitalist, titled his talk “Rational Hope”. He spoke to an audience largely comprised of industry leaders and scientists about research breakthroughs, citing PKU and Gaucher as historical examples of a treatment coming to market successfully and in a relative quick manner. I believe his end goal was to illustrate how exponential advances in science have shortened the lab to patient timeline allowing today’s patients to have rational hope for a treatment.

Rational Hope.

I could not digest the term. I still can’t. It has been rolling in and out of my thoughts for days. I am trying to justify it with my own personal experience as a parent of a child with a rare terminal disease, as a funder of research 20+ years in the making that is now in clinical trials, as an advocate for families still caring for children who have terminal conditions, and as a friend to far too many bereaved parents. Rational hope…..what the fuck is that??!!

If we qualify hope, then his term must imply that some hope is irrational. And this is the nit, the thing that is getting my britches in a bundle.

When Ben was two years old, just diagnosed and barely uttering a word, was my hope that he might learn to communicate and my efforts to teach him sign language, utilize communication boards and utter a word during one of his weekly speech therapy sessions irrational because science had illustrated that I could expect that he would either never speak or in time lose all speech?

And were those physical therapy sessions, horseback riding lessons and the table stander in his last years, all in place with the hope of maintaining his core strength, in vain or irrational because science said we could not expect that strength to last?

Then there is the science.

I know that when I started Ben’s Dream—a foundation to fund research—my hope was to find a treatment that would benefit my child and all the children like him. I also knew, even then, with a perfectly healthy looking two-year-old in my lap, that I could not expect the science to get there in time. Was that hope misplaced and therefore irrational?

As Sanfilippo took more and more of Ben and his functions declined, one could argue that my hope transitioned; moving away from an expectation of saving my son and toward the greater goal of providing a better future for other parents of children with Sanfilippo. Since hearing the term rational hope, I have thought particularly hard about this time in my life; questioning deeply if the hope that drove me to continue to fundraise and support critical research was the same hope that had pushed me to be a better mom to Ben? And if it wasn’t the same hope should I consider this new hope more rational because I could expect the outcome (gene therapy for children with Sanfilippo) to become a reality? Did expectations met or ones unrealized somehow negate my early hope and qualify it as irrational? And how do I rectify that with hope I feel today even though Ben is gone. Most days, I wake up hopeful expecting something joyous to happen even while I carry a great weight of sadness. Is this hope yet another new hope and is it rational?

Here is what I have concluded.

I simply have hope. Not a qualified hope. Just hope standing all on its own. HOPE. I believe hope is ALWAYS rational. He should have titled his speech “Rational Expectation”.

A few post scripts:

Ben did speak, saying his last word “Boobies” around age 14. I am so glad I have hope and that it pushes me everyday because that is a memory I will never forget. Ever.

I had the luck of meeting the presenter at another event just a few days later. He agreed to meet with me to discuss hope. I will keep you posted.

Category: Sanfilippo syndrome (MPS)

I’ve been lucky to have only had two jobs in my adult life. This consistency in my work has allowed me to deepen the meaning of my work as a physical therapist, eventually learning to look beyond the textbook definition. I have spent time as both hospital and school PT working with kids through a range of age, health concerns and diagnosis. PT is very focused on the “fixing”. We create care plans and set specific goals for improvement that push our work towards increasing the ability to better participate and enjoy daily life.

I’ve shared the journey of many kids and young adults who have severe, life-limiting illnesses. There needs to be a pause here. Sharing the journey inspires, sustains and fulfills me. I’ve partnered with parents and my school district to broaden the sometimes boxed in definition of what it means to service children in the school and out of district school settings. This means that besides the already awesome job of being a pediatric PT and working with kids to improve their function in order to maximize their access to the school environment, I have been an advocate, supporter of family’s needs, an educator to families and staff, a bridge to the medical world and, simply a person who has learned to “hold space” with someone.

When I met Ben, a preschool aged boy with Sanfilippo Syndrome, I had not yet begun to hold space. I had set many goals and was working hard to increase his flexibility, helping him get stronger so he could transition from the rug more quickly and use a mature pattern on the stairs with his classmates. I was searching for more supportive seating that would allow him to stay seated longer during tabletop activities in school. I was making sure he was able to safely access the playground. I was definitely in a “fixing” mindset.

Early in Ben’s elementary school career, it was clear that the public school setting was not the best place to meet his needs, and he transitioned to an out of district placement. Years later, we reconnected at his out of district placement; an unexpected gift. This new setting challenged me to think outside my previous role as his PT. The classroom was different, the expectations were different, and my mindset had to be different too. Preventing loss of function became a priority. Seating, positioning and comfort mattered a lot, as did getting outside and accessing the playground with assistance. As we worked together, I talked about things we used to do, books I know he loved, and the farm animals I had recently seen. I stayed a few minutes longer. I found myself just being with Ben, holding space in a familiar, comfortable way.

Early in Ben’s elementary school career, it was clear that the public school setting was not the best place to meet his needs, and he transitioned to an out of district placement. Years later, we reconnected at his out of district placement; an unexpected gift. This new setting challenged me to think outside my previous role as his PT. The classroom was different, the expectations were different, and my mindset had to be different too. Preventing loss of function became a priority. Seating, positioning and comfort mattered a lot, as did getting outside and accessing the playground with assistance. As we worked together, I talked about things we used to do, books I know he loved, and the farm animals I had recently seen. I stayed a few minutes longer. I found myself just being with Ben, holding space in a familiar, comfortable way.

In those months and years of service, I let go of some of the priorities I once had and grew to care an awful lot about what was important for Ben and his parents. Like a daily routine of sitting up at the edge of a bed or couch together to chat at the end of a day or read a book. We worked tirelessly to find the right positioning, and the strength to maintain an upright sitting position. I knew his time sitting next to someone, parents and teachers was time Ben still enjoyed. I wanted to be sure he kept this joy for as long as possible. Improving access to traditional education lost some importance. Life experiences replaced traditional educational goals because our focus was now on his quality of days. And we needed Ben to have as many of those as possible. I consulted on seating, positioning and movement activities/stretching as needed. I stayed a few minutes longer. I couldn’t fix any of this. But I could walk along in the journey, and just be present.

In the course of my work, I’ve thought a lot about the parents and families I have met. For most of them, I think there is nothing linear about their journey. I watch as acceptance and denial race along like a roller coaster of ups and downs. I think there are times during this journey that a provider (teacher, doctor, PT etc) can have varying impact: sometimes no impact at all, and sometimes, we can actually make a difference for a child, and for a family with our words, and our knowledge. When we meet, I try to remind myself of this, and always consider what parents bring to the table, and where they are in their journey. I try and put their agendas first, as I consider how to move forward. I have found that I can shift goals to meet changing needs as children move to a new baseline. I now know that I do not have to be the “fixer” all the time, and that the other layers of being a PT are equally important and fulfilling. Finding the right words, at the right time, and presenting them in the right way is the challenge. I don’t always do it right. When I do, it all feels worth it. Sharing the journey, I know is worth it.

In the course of my work, I’ve thought a lot about the parents and families I have met. For most of them, I think there is nothing linear about their journey. I watch as acceptance and denial race along like a roller coaster of ups and downs. I think there are times during this journey that a provider (teacher, doctor, PT etc) can have varying impact: sometimes no impact at all, and sometimes, we can actually make a difference for a child, and for a family with our words, and our knowledge. When we meet, I try to remind myself of this, and always consider what parents bring to the table, and where they are in their journey. I try and put their agendas first, as I consider how to move forward. I have found that I can shift goals to meet changing needs as children move to a new baseline. I now know that I do not have to be the “fixer” all the time, and that the other layers of being a PT are equally important and fulfilling. Finding the right words, at the right time, and presenting them in the right way is the challenge. I don’t always do it right. When I do, it all feels worth it. Sharing the journey, I know is worth it.

Beth Quinty worked for 10 years as a physical therapist at Boston Children’s Hospital. She currently works in a public school in MetroWest Boston. She is the mom to three children.

If you are interested in contributing a blog please email connect@courageousparentsnetwork.org. Our upcoming topics are marriage, voice of the father, making memories, participating or not participating in a treatment.

Category: Sanfilippo syndrome (MPS)

Our daughter, Blair, was born with a progressive terminal disease called Sanfilippo Syndrome. When she was diagnosed at age six, our pediatrician mentioned palliative care and hospice to us. We really didn’t think it applied to us since she was not near the end of her life. Fortunately, a mom in the Sanfilippo Syndrome community explained to me the benefit of having palliative care on board BEFORE my daughter was too progressed. She suggested that it would be beneficial for the doctor to get to know Blair and our family early in the process. That way we could establish a relationship with him and he would be able to better guide us through the process when it was time. We could not be more thankful for that advice.

For several years, we met with the palliative care doctor only a few times a year for him to simply check in with us on Blair’s health. Over time he began to touch on topics that we would need to think about and be prepared for as our daughter progressed. The office provided a safe place for us to discuss extremely difficult decisions like signing a Do Not Resuscitate form. Our doctor and his team listened carefully, authenticated our feelings, and supported our decisions.

We were thankful to have established this relationship when Blair was diagnosed with gallstones and her gall bladder needed to be removed. It is extremely risky for a fifteen year old with Sanfilippo Syndrome to have anesthesia. Our palliative care team was able to schedule a meeting for us with Blair’s surgeon, neurologist, geneticist and gastroenterologist in order to make the best decision for her. This meeting helped give us confidence in our decision to go through with the surgery. It would have been highly unlikely we could have coordinated such a meeting without the support of palliative care.

During the last four months of Blair’s life, she had very complicated symptoms of discomfort that were extremely difficult to diagnose. She was having uncontrollable movements most of the day, large amounts of secretions, extreme weakness, and feeding difficulties. We rarely changed her out of her nightgown to try to keep her as comfortable as possible. She would have been miserable if she had to be taken anywhere in the car or in her wheelchair since she would either be moving uncontrollably, flopped over due to the weakness, or choking on secretions. Palliative care really became invaluable to our family at this point. Rather than transport Blair around to several doctors’ appointments to figure out what was going on and how to help her, our doctor began coordinating all of her care. He came to our home to check on her and reached out as needed to her specialists. We could call the doctor around the clock as needed, and trust me we did. The doctor was always calm and supportive no matter what time we called.

The palliative care coordinator checked in with us regularly during those months. She would often ask what could be done to help us. After several conversations, she picked up on our lack of sleep and offered to help get us nursing at night. Our insurance company had never approved nursing, but she somehow got it approved. She was so helpful, and even understood when I couldn’t get comfortable with hiring a night nurse for Blair. She just continued to support us.

About a month before Blair passed away, the palliative care team came to our house and we all agreed that it was time to bring in hospice. Palliative care coordinated all of Blair’s hospice care making the transition seamless. Since Sanfilippo Syndrome is so rare, it is doubtful the hospice doctor would have ever had a patient with it and with all the stress we were under it would have been difficult to deal with a new doctor. We received all the benefits of hospice care while still having palliative care. That also meant there were fewer new people in our home and that this doctor that we had spent years forming a relationship with would be by our side at the end of Blair’s life.

Thinking about our relationship with the palliative care team truly brings tears to my eyes. They knew us so well and we trusted them fully to help guide us through the process. They prepared us along they way with baby steps and never judged us on our decisions. Instead, they were both supportive and encouraging regarding our care for Blair. They cared deeply for our daughter as well as the rest of the family. We could not be more thankful that our children’s hospital has such a wonderful palliative care team. We cannot imagine going through that difficult time without them.

Category: Sanfilippo syndrome (MPS)

I met my future husband Sherin in a London pub, hours after returning from India, and three months after fleeing the U.S. to avoid attending law school. I was getting ready to return home to Michigan in August 1991, having just arrived back in London after two weeks in India. But after a few dates with Sherin, I decided that I would stay a little longer in the UK, after all. This eventually turned into a year, with even more travels to Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Portugal, and France, until I was forced, by my visa limits, to return to the U.S. But I really knew by then that I would not go to law school.

We married in 1994, and I became a psychologist, which I always knew I wanted to be. We lived in London until 2001, until our first daughter Lucy was 3 and when I was pregnant with our second child. It seemed the right time to move closer to family, as our own family was growing. In July 2001, Ben was born in Pontiac, Michigan, in the same hospital my mother was born 57 years prior.

Sherin and I had spent 10 years traveling together (Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, all over Europe), and the last three with Lucy, who we took to India and Egypt. We didn’t expect our lifestyle to change with Baby 2. But Ben started exhibiting signs of what would eventually be named Schwartz-Jampel syndrome, a rare neuromuscular disorder, days after his birth. We did travel throughout the U.S., but our journeys took us to top hospitals in Ann Arbor, Baltimore and Boston, to figure out his diagnosis and to start a life of consultations and complicated medical procedures and surgeries. We managed fun trips whenever possible, carting respiratory and walking equipment and even ordering oxygen for long plane rides as needed, including back to London in 2004 to visit friends. However, a trip to San Francisco in July 2007 almost made us stop traveling forever.

First, one of our bags was lost. While I always tried to distribute durable medical supplies throughout our bags, this time there was one bag that held more stuff, such as tracheostomy suction catheters, than others. When we found out it was this bag that was missing, and which may or may not arrive on the next flight three hours later, I nearly fainted. It did arrive, and we managed to carry out our family vacation. On our return to SFO, however, TSA agents—despite one of the busiest, longest lines I had seen in any airport—made me remove the hip-to-ankle leg braces that Ben was wearing before I could walk with him through the metal detectors. While removing Ben’s shoes and clothing in order to take off these braces, while Charlotte, our youngest child at 20 months old, screamed to be held and hundreds of other travelers watched, I thought “I am never, ever doing this again”.

For four years, we didn’t step foot on a plane. This pained me, but I was steadfast. We purchased a wheelchair accessible van in early 2009, and from then on, if we wanted to travel, we did so by car, to Washing ton D.C., Orlando (with many stops along the way), Montreal, Maine, New Hampshire, Michigan, New York, Ohio and Pennsylvania. We even figured out how to spend a week at Sandbridge Outer Banks, near Virginia Beach, renting a beach wheelchair from a local company who delivered it to the house we were renting. It was hard to find enough fun things for Ben to do at the beach—city travels are more his thing because he loves learning about history and he prefers being inside (glaucoma and certain medications make sunlight pretty difficult for him to bear). Yet we knew that some of our family’s travels needed to focus on our active, outdoor loving girls.

But after Sherin’s mother died, he felt the pull of Germany, and really wanted to take his now older children to see his mother’s homeland. I adamantly refused. There was no way I was going to suffer further humiliation and discomfort by airport security. He was patient in his attempts to change my mind, and finally, I acquiesced. To my complete delight, I realized that now, in 2011, traveling abroad was an easier, more disability-friendly experience than we had ever experienced in the United States. Ben was treated with respect. Accommodations were made for equipment, medicine was tested without fuss, and we were not rushed along. Lucy and Charlotte were escorted by friendly staff. People smiled. And no bags of equipment were lost, and no equipment was broken. I was finally able satisfy my hunger for travel, with all of my children in tow.

But after Sherin’s mother died, he felt the pull of Germany, and really wanted to take his now older children to see his mother’s homeland. I adamantly refused. There was no way I was going to suffer further humiliation and discomfort by airport security. He was patient in his attempts to change my mind, and finally, I acquiesced. To my complete delight, I realized that now, in 2011, traveling abroad was an easier, more disability-friendly experience than we had ever experienced in the United States. Ben was treated with respect. Accommodations were made for equipment, medicine was tested without fuss, and we were not rushed along. Lucy and Charlotte were escorted by friendly staff. People smiled. And no bags of equipment were lost, and no equipment was broken. I was finally able satisfy my hunger for travel, with all of my children in tow.

Since then, our family has tried to make one international trip per year, to England, Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, France, Italy, and yes, back to Germany. To some, this may seem decadent, but the cost is nearly the same as that of traveling in the U.S. when you rent a home through AirBnB or VRBO and are then able to eat two meals at “home”. We look for flights many months in advance and compare prices before settling on a deal. And with lower cost but reliable airlines like Norwegian (which we have flown twice), you can fly to Europe for the same as a flight to California (but we all know I’m not flying to California again). We never fly a U.S. based airline when going abroad. They have broken equipment on the way to other states, including during a short 1.5 hour flight to Detroit. We just can’t trust them.

Our experiences in these countries have been almost always welcoming, but Rome was tough. We knew it would be. Luckily Lucy, who was by then 16, was strong enough to help us lift Ben’s wheelchair, and we visited the Vatican museum in the early part of the trip before we were exhausted (the “accessible” Vatican tour means you miss most of the sights. Why travel all that way and not see all that art?). The walk upstairs/walk downstairs route of the Vatican tour was exhausting and must be for thousands of people each year. It’s not a wonder that we never saw one power wheelchair throughout Rome—it would never work, without curb cuts or over those crazy cobblestones—and the manual wheelchairs we did see often suffered hardships (we witnessed two men trying to put a wheel back on a man’s wheelchair). But Ben, a Latin student, really wanted to go. Ironically, one of the oldest places in Rome, the Coliseum, has an elevator. But that can’t be said for most Roman sights.

Ben was also the force behind our Iceland trip, asking to see the Northern Lights. He requested to go in February one year, before major spine surgery. If you can stand sideways rain, you will love Iceland in February. It was indeed spectacular, and beautifully accessible, and whose body won’t benefit from the geothermal 104F degree silica springs? This was pure heaven for someone with a neuromuscular disorder. For a country of 300,000 people (200K in Reykjavik), Iceland has made universal design the hallmark of their land outside of waterfalls and volcanoes. Ramps are seamlessly built into town squares and busy streets. If you don’t have an eagle eye for accessibility—which one gets after being with a loved one who uses a mobility device– one would never notice them.

Ben was also the force behind our Iceland trip, asking to see the Northern Lights. He requested to go in February one year, before major spine surgery. If you can stand sideways rain, you will love Iceland in February. It was indeed spectacular, and beautifully accessible, and whose body won’t benefit from the geothermal 104F degree silica springs? This was pure heaven for someone with a neuromuscular disorder. For a country of 300,000 people (200K in Reykjavik), Iceland has made universal design the hallmark of their land outside of waterfalls and volcanoes. Ramps are seamlessly built into town squares and busy streets. If you don’t have an eagle eye for accessibility—which one gets after being with a loved one who uses a mobility device– one would never notice them.

We never thought we could top Iceland’s accessibility, until we visited Oslo and Bergen. It was the first place where we did all of our city travel by foot, boat, train, or bus. Without asking for special treatment, train conductors, captains and bus drivers would spot us in a crowd and escort us to the front of the line, allowing us to board before others. We were in travel heaven.

But in April 2017, we traveled to Berlin, Sherin’s mother’s birthplace. We had visited other parts of Germany on our previous trip in 2011—the Black Forest (not accessible), Freiburg and Konstanz (both gorgeous and fairly accessible). I’ve now termed Berlin the world’s accessible capital. Having rebuilt most of its city over the last 30 years, the people of Berlin have made their entire, extensive S-bahn and U-bahn train system nearly 100% accessible. The trains line up nearly perfectly with the station platform. Elevators are present at all but a handful of stations. And it was hard to find an inaccessible location anywhere. I found myself thinking of now 15 year old Ben’s adulthood. Could this be his prospective home? He’s a German citizen by birth through Sherin, and he speaks German fluently. This country, which committed the most unspeakable acts 75 years ago, might just be my son’s future.

Traveling with Ben has allowed us to really experience a country’s and a culture’s attitudes towards its most vulnerable citizens. Psychologists often talk about “helping behavior”, which many countries we have visited exhibit through accessible planning and kind citizenship, thereby creating a culture of inclusiveness. Nothing about traveling with physical and medical challenges is easy, but if you want to travel outside the U.S., you can’t go wrong in Northern Europe. Our girls would love to travel to tropical, adventurous places and they wonder why we can’t plan those kinds of trips. Accessibility is the answer, of course, and it does sadden me that a trip to Costa Rica or Mexico, with its challenging terrains, seems impossible. But Ben, who also studies ancient Greek, would love to visit Athens. Sherin and I honeymooned in Athens and the Greek Islands. We backpacked through Santorini, Samos and Paros. We can recall that accessibility is not a hallmark of Greek design. Can we make it to Athens with Ben? Whether it is Athens, Costa Rica or Mexico, we should probably try to go, and soon, before we and Ben get older.

Category: Sanfilippo syndrome (MPS)

In the aftermath of losing my only child, the discussion of what my path will be moving forward is a hot topic. With a medically fragile child, my purpose was very defined. He required a level of care which did not make a career feasible for me, and truth be told, I was not a bit career-minded despite having earned an engineering degree. I was 100% motherhood-minded and that was exactly what our family needed from me. Now that Miles has been gone for 20 months, I get the sense that people are starting to get uncomfortable with me neither mothering nor working. They are wondering what path I will travel now that Miles is gone. Guess what? So am I! I truly have no idea what to do with my life from this point forward, and the slightest nudge or suggestion regarding the topic makes me very uncomfortable.

We all want to be on a clear path. When we’re off path, the weeds are high, our views are obscured and our destination is unclear. To give you an idea where I feel I am right now, I’d say I’m lost at sea. You guys. I’m not even anywhere near dry land. Forget the clear cut path, forget the bug-infested weeds surrounding it, forget the final destination and the landmarks along the way. I’m in the freaking ocean. Alone. Sometimes you come out for a swim and we speak. I act normally because I’m trying to find joy in my current circumstances. I’ll tell you a funny story because I love to make you laugh. I’m close to drowning, but I’m still trying to be thoughtful and kind to those around me. I don’t ask you for help because I know that I am solely responsible for working through my grief, my doubts, my anger, my loneliness. I am buoyed by God and my faith that He is actively working in my life and wants me to reach dry land. I still flail regularly and often feel that the shore is non-existent, or at best, farther away than I could ever swim in a lifetime.

I want to make it to shore. I really do. My fingers are pruning pretty badly out here. It’s cold and treading water is exhausting. Keep coming by to check on me, but please understand that there is no way for you to drag me out. It just doesn’t work that way.

I’m confident that I will roll in like a beached whale at some point, and hopefully soon! Until then, try not to force me onto a path. We can talk about that when I’m digging the sand and seahorses out of my pockets and warming up by the fire.

Thanks for loving me through this and understanding that the grief process is wildly unpredictable, messy, awkward and uncomfortable. And I plead with those out there that have lost a loved one and have forced yourselves onto a path to avoid the grief altogether. Please know that you cannot beat the system. You cannot skip the “lost at sea” portion of the program and go on your merry way, stuffing your feelings down, down, down. You may travel comfortably down your path for awhile, but it will inevitable deposit you directly into the depths of the ocean with no warning. Take care of yourself by acknowledging your loss. You owe it to yourself and to those around you.

Category: Sanfilippo syndrome (MPS)

Seven months after my son Benjamin’s diagnosis with a progressively debilitating and eventually terminal disorder, I was pregnant with my third child. Those 7 months and the subsequent first 4 months of pregnancy were ones fraught with anxiety, sadness, and fear.

Looking back some 19 years later, I now realize they also contained determination and hope.

A few weeks after my 15-month-old son’s diagnosis with Sanfilippo Syndrome, and before I became pregnant again, we scheduled an appointment with a medical geneticist. Sanfilippo is an inherited genetic disorder. I remember sitting in the counselor’s office as she perfunctorily explained what the internet had already told me. My husband and I both carried a defective gene and each time we conceived a child we had a 25% chance of having a child with the same condition. She matter-of-factly presented alternatives – sperm donation or adoption. We discussed prenatal testing options – back then only amnio was available and even that was only 90-95% accurate. We shared that we had dreamed of a larger family, hoping that she would offer words that would build our courage and help us find our way of making that dream a truth. Instead, what she offered was both unprofessional and paralyzing advice. It went something like this – we should be happy our oldest child, Noah, was not affected, that Benjamin and the progressive nature of his disorder would require so much of our time and attention that we would have little left to care for Noah much less another child. In essence, she was telling us that it would be irresponsible (I think the word she used was unfair) to bring another child into our family.

That night in bed, I wept tears I did not know I had. I thought I had cried them all out in the days after Ben’s diagnosis. My husband Stuart held me as I sobbed. When words could finally find their way out, I was able to tell him that I was crying for all the children I would never have, for the eggs that would go unused and for the dreams of a big family, a dream that was now broken. My tears that night came with such ferocity because I felt completely undefined and without hope for the future.

Ironically, I had an appointment with Ben’s pediatrician a few days later. The words of the geneticist haunted me and I needed to discuss it with someone. So, I told her what the geneticist had said. With Ben sitting on my lap, she reached over and hugged the both of us, and assured me of the ridiculousness of the counselor’s advice. The child, however it came to our family – by birth or by adoption – would only know our family (warts, bumps, dying sibling and all) and if we were determined in our capacity to love, we should have another child. She added that it was not irresponsible – it would add richness to Ben’s life, and bring companionship to Noah. As she told me about all her other patients with special needs, the other vibrant families, I felt hope returning and a sense of determination growing.

Over the next several months, Stuart and I met with a genetic counselor and engaged an obstetrician who specialized in high-risk pregnancies. We reviewed the profiles of possible sperm donors (cutting one of us out of the genetic loop removed the risk of another child with Sanfilippo). We met with an adoption agency. And Stuart and I had many long conversations about the possibility of another biological child. We agreed that we did not want to bring another affected child into the world and adoption or sperm donation pretty much assured that. A twenty-five percent chance seems small but when you’ve already hit those odds once it looms very very large.

I have always been pro-choice, believing that every woman should have that right. However, I never thought it would be a choice I would need to make. I was trying to sort out if I could terminate an affected fetus. I had been pregnant twice before. I knew that by 18-22 weeks, I would be feeling movement inside of me. And for me this was all complicated by guilt – wasn’t choosing not to have another child with Sanfilippo somehow denying the child I so desperately loved and did not want to die? I’m not sure if Stuart didn’t have that guilt or if he was just more confident in his ability to not have regret, but I knew that going down the biological path was going to require that I make the final decision.

I am not sure what eventually tipped the scales and made me choose to roll the biological dice. Perhaps the unknown but inherent risks in both sperm donation and adoption felt somehow riskier than my 25% chance. Maybe it was that finding a doctor who felt confident in the results from an amnio done at 14 weeks rather than the standard 18 weeks gave me courage. Or maybe it was simply that I just could not give up on that dream of another pregnancy. In December I was pregnant.

The weeks between the amnio and the results were as one might expect — horrid. The testing was being done in another state, and the doctor would communicate them directly to Stuart. I started to separate myself from my feelings and saw a rising fear in my husband’s eyes. I only really remember three things from that time: when a friend seeing my growing bump asked if I was pregnant and I stumbled as I tried to hide the truth; a song on the radio whose lyrics captured how I felt (something about a long December and oysters with no pearls); and standing in the dining room as Stuart gave me the results.

That summer our daughter Isabelle (which means In the favor of God) was born. And our pediatrician was right. For her, this is our family. And she loved Ben fiercely – caring for him like a second mother. Together, she and Noah will continue to hold his memory and strengthen one another. For me, I let her birth and the LUCK I felt that she was unaffected fill my heart and complete my family.

Category: Sanfilippo syndrome (MPS)

I am part of a club; one I did not ask to be a part of; one whose membership means sharing unconditional love with a courageous innocent soul. A membership where you can only wish that you are able to savor every moment, memory and smell of your child.

Membership will mean you will watch a vivacious child forget how to walk, how to talk, how to eat…. how to laugh. The membership will mean you will watch your child suffer from pain, seizures, involuntary movements, inability to handle their own secretions and where one day they will no longer engage with you and the world around them.

No, I did not ask to be a part of this club but I am. Membership has taught me to live for today, to love hard with all my heart, to smile on days when all I want to do is cry. It has showed me I can fight for my child, for others like him and to be his, and their voice.

This membership does not make it any easier when I look for words to share with other members who must say their goodbyes nor do I think it has equipped me with what I will need when it is time to say my own.

I am in a club that has bound me by the heart and soul with many other mothers and fathers who want nothing more than to box a lifetime of memories into a short period of time. The families I have met along the way have given me a lifetime of strength and love. The mothers I have met have made me stronger.

I am part of a club that is waiting for the day that a cure will mean a different road traveled for families just receiving their membership. I am part of a club where many children have fought ~ are fighting, will fight. Sanfilippo Syndrome gave me a lifetime membership.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Stacey Montgomery is mom to Mariah age 26, Chelsey age 22, Hailee age 20 and grandma to and Faith. Her son Lucas, now 19, soon to be 20 on July 31st, was diagnosed at age 8 with Sanfilippo Syndrome, a degenerative and fatal genetic disorder. Parenting Lucas has included an active role in fundraising for a cure for Sanfilippo Syndrome and connecting with the other parents of children with life-limiting illnesses to be a resource. The words she shared are part of her up coming memoir, Be Unbelievable

Category: Sanfilippo syndrome (MPS)

My name is Noah Siedman and I have been an older brother to two siblings for 20 of my 23 years. My younger brother Ben had a rare genetic disorder called Sanfilippo Syndrome, a disease that three years ago resulted in his death. I have spent a long time thinking about my brother; what he taught me, how I could best help him and how to honor his memory now that he is gone. I do not by any means have it all figured out, but I have found a few truths that have helped me understand and move forward. They are truths that have withstood all the hardship that I have faced.

The first truth is this: we are equal to the challenges we face, and we are stronger for them, if only so that we can face what the next day brings. As siblings, we deal in the “most we can handle every day”. We are called upon to be the most innovative we can be, to display the most patience we can muster, to be the most composed person in the room. We do everything right up to the very limit of what we can handle.

I tell you this truth with the assumption that at some essential level, you already know it. You have lived or are living with the most you can handle every day. Each day, you have faced challenges and overcome them. I bet sometimes it is years later before you even realize just how insurmountable an obstacle that you left behind. And, you know that while tomorrow’s challenges might loom even greater, you go to sleep with every intention of being their equal when you wake. That is what we, siblings, do.

I remind you of your strength – this knowledge that we are equal to the challenges we face because you will need it to do what I ask of you next – my second truth. Stop being afraid. Stop being afraid to be angry. Stop being afraid of forgetting. Stop being afraid of getting fed up, of being sad, of giving up hope. As siblings, those fears are our constant companions. They keep smiles on our faces and give us energy to face each day but they also make us toss and turn at night and sow doubt in everything we do.

I spent most of my life with that fear; asking myself at every turn if I was doing enough; was I a terrible person when I lost patience with my brother or if I can’t remember the good. I saw what fear did to my family and friends; how amid all the love and support, the struggles and successes, we were all strung-up by the same tension, the same fear. Even today, three years after my brother’s death, I am still afraid of things so far beyond my ability to change that I cannot fathom why I let them remain tenants in my brain. That fear has planted itself so deeply that at times I even wonder if it was love and strength that moved me to be there for my brother or fear.

I think we live with that fear for so long that we question everything. But I know this. Fear of being angry becomes resentment. Fear of forgetting becomes dependency. Fear of failure leads to avoidance and fear of losing hope becomes apathy. These things are so much worse than their causes and so much more avoidable.

I don’t suggest that you embrace these emotions because they are not so bad as you think, but because each moment lived without fear is one where you are in control. Every second you regain from fear is one you can spend however you like. It is the time where you can make meaning and grow, where you can make memories that you will never lose. As siblings, I think that is our real battle, not the everyday challenges of living with a sibling with special needs but this internal one.

I implore you to never forget that you are equal to your challenges, and to always know that the enemy of happiness is not hardship, but fear. I don’t doubt that this advice is hard to hear and even harder to follow. Know that you have already proven that you have the strength to do it and that each little success makes the next come easier.

Category: Sanfilippo syndrome (MPS)

I have been journaling a lot over the last week. It started with a list of things I would have liked to do with Ben on his 21st birthday (like share a beer) if Sanfilippo had never been part of the equation. It moved to a poem about the things I knew about Ben despite Sanfilippo (like he would always laugh with his whole being). And like most things Ben encouraged me to do, all this quiet time writing ended with a feeling of resolve, action and determination. Over the years, journaling has helped me cope with the transitions Ben experienced, sort out the feelings in my heart and guide the decisions at hand. The simple act of writing this list let me embrace the pain of what would never be, step away, and see all that I loved and knew about Ben. In some sacred way, writing this list let me enjoy envisioning Ben and I together on his birthday.

Happy Birthday my Ben!

Twenty-One.. I Wish I May, I Wish I Might…..

- Hug him strong.

- Tell him I am proud of the man he has become

- Do a shot of Jack Daniels with him

- Eat crispy spicy beef and fried rice

- Share a pint

- Watch 3 episodes of Arthur

- Walk the 2 black dogs

- Listen to his plans to spend a semester farming in a foreign country

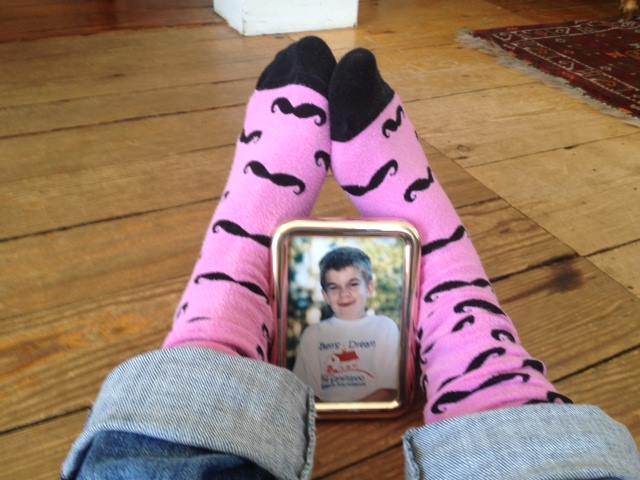

- Send him a pair of socks with boobies on them

- Learn about his most recent fraternity antics

- Hold his hand

- Laugh with him until I wet my pants

- Tell him the story about the day he was born and why his name is not Owen

- Make him a Jackie sandwich

- Tease him about how he always grunted when he ate as a toddler; loving his food so much

- See my father’s eyes when I look into his and know he has the same sense of loyalty

- Ask about his most recent girl – likely a steady!

- Make him chocolate cake with chocolate frosting

- Listen to the sound of his voice

- Get excited about his excellent bracket choices

- Whisper I love you in his ear